The arid Southwest has a proven model, the acequia, for water use that is local, democratic, and resilient to heat and drought.

The arid Southwest has a proven model, the acequia, for water use that is local, democratic, and resilient to heat and drought.

April 22, 2025

Acequia de los Vallejos in southern Colorado’s San Luis Valley. (Photo courtesy of the Acequia Institute)

A version of this article originally appeared in The Deep Dish, our members-only newsletter. Become a member today and get the next issue directly in your inbox.

Expand your understanding of food systems as a Civil Eats member. Enjoy unlimited access to our groundbreaking reporting, engage with experts, and connect with a community of changemakers.

Already a member?

Login

On a stormy spring day, Devon Peña stood atop a sagebrush-covered hill and looked down on Colorado’s San Luis Valley. Dark clouds had unleashed a deluge just a few hours earlier, but now they hovered over the mountains, veiling the summits above.

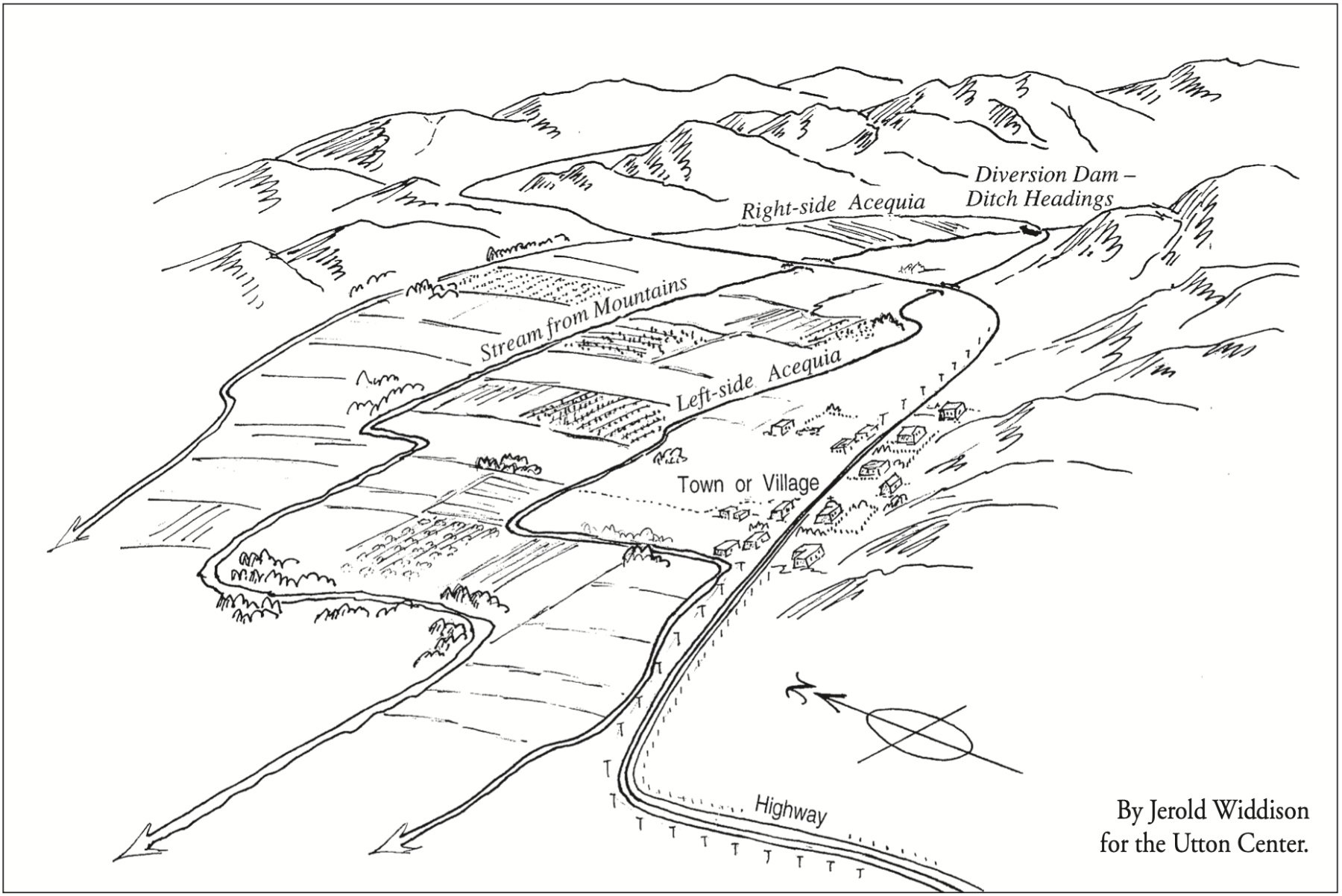

Below, rows of long, narrow fields extended from Culebra Creek toward a man-made channel, the main artery of the valley’s centuries-old “acequia” irrigation system. This was the “People’s Ditch,” a waterway holding the oldest continuous water right in Colorado. The channel carried water from tributaries of the Rio Grande, high in the Sangre de Cristo mountains, down to the fields below.

There, the flow was diverted into smaller ditches that irrigated fields of alfalfa, cabbage, and potatoes, the water seeping naturally through the earthen walls. In the San Luis Valley as a whole, 130 gravity-flow ditches irrigated 30,000 acres of farmland and 10,000 acres of wetlands.

“This is an incredibly productive, resilient, and sustainable system,” said Peña, founder of The Acequia Institute, a nonprofit that supports environmental and food justice in southern Colorado.

“[Water managers] are starting to appreciate us a lot more than they did 20 or 30 years ago when they thought we were backward, primitive, and inefficient.”

The acequia system was once dismissed by Western water managers. But as a changing climate brings increasing drought and aridification to the Southwest, time-tested solutions like this one could hold the key to mitigating the worst impacts of climate change, especially in rural communities.

“[Water managers] are starting to appreciate us a lot more than they did 20 or 30 years ago when they thought we were backward, primitive, and inefficient,” Peña said.

Water management in what is now New Mexico dates back to at least 800 A.D., to the Pueblo people, who used gravity-fed irrigation ditches for their crops. The acequia system, which arrived with Spanish colonizers in the 1600s, is not merely hydrological. It is political, even philosophical.

An illustration of how acequias work. (Illustration credit: Jerold Widdison for the Utton Center at the University of New Mexico)

The word acequia—from the Arabic word “as-saquiya,” which means “that which carries water”—was used to describe the irrigation ditches that evolved in the Middle East and were introduced to the Iberian Peninsula during the Islamic Golden Age. In New Mexico, these systems were often put in place even before a church was built.

Acequias operate under the principle of “shared scarcity,” rooted in Islamic law, whereby every living thing has a right to water, and to deny them water is a mortal sin. Water is thus treated as a communal resource to be shared, rather than divvied up and contested.

“They all share something in common, which is community governance,” Peña said. “It’s a water democracy.”

An acequia is both a physical canal system and a political structure, which includes an elected mayordomo, or ditch boss, along with commissioners who govern management and operations. Acequias are self-sufficient and collectively owned by members, each with water rights to the ditch and an equal vote regardless of property size.

The Spanish built acequias throughout the Southwest, but most in Arizona and California were abandoned or replaced by modern irrigation systems. In Texas, a few remain, including the San Antonio Mission Acequias.

“Our ancestors and predecessors created a cultural landscape and spread a broad ribbon of life that is an extension of the river,” said Paula Garcia, executive director of the grassroots New Mexico Acequia Association. “They have literally shaped the landscape.”

Acequias are central to the system’s resilience and adaptability, New Mexico State University hydrologist Sam Fernald said. “By having people on the ground, connected to every drop, they are able to adapt,” he said. “They have been adapting to changes in water and land for 400 years.”

Unlike conventional irrigation systems, the physical design of the acequias mimics natural hydrological and ecological functions, slowly distributing water throughout the landscape through unlined ditches that allow seepage. This “keeps surface and groundwater connected,” Fernald said, recharging the aquifer, reducing evaporation and aridification, enhancing biodiversity, and returning flows to the river.

Modern management of rivers for commercial agriculture has reduced this connectivity through channelization, levees, and dams. These have stopped streams and rivers from meandering into the floodplain, reducing aquifer recharge and late-season groundwater return.

But the modern system is under stress, as a changing climate reduces mountain snowpack, the main source of Western water. Snowpack acts as a water bank that holds frozen water in the mountains into the spring and releases it throughout the summer. Changing climate patterns also mean shifts in melt patterns, and all of this makes managing water flows through dams a challenge.

“They all share something in common, which is community governance. It’s a water democracy.”

Adding to the uncertainty, the Trump administration is making cuts to the Interior Department’s Bureau of Reclamation, which manages dams, and President Donald Trump has shown a willingness to demand water releases himself, as he did recently with two dams in California, to the consternation of farmers and water managers.

“The acequias and Rio Grande have given life, food, and shelter to people and wildlife, but they’re at risk if we don’t value and better adapt these systems and ecosystems for future conditions,” said Yasmeen Najmi, a planner for Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District, which helps manage irrigation in the valley, including the acequias.

Industrial agriculture exacerbates climate change through its use of synthetic fertilizers, whose production generates significant fossil-fuel emissions, and soil tillage, which disrupts soil’s ability to capture carbon. According to José Maria Martín Civantos, an expert in landscape archaeology at the University of Granada, in Spain, this kind of agriculture is “literally building the desert.”

By contrast, traditional irrigation systems like acequias enhance water quality, expand wildlife habitat, increase soil fertility, and—crucially—support highly productive food systems.

After New Mexico was ceded to the U.S. in 1848, Americans quickly recognized the productivity of acequia agriculture, said Sylvia Rodriguez, an anthropologist and author who grew up in an acequia community in Taos, New Mexico. “American takeover incorporated the acequia system into the state statutes because it was so efficient. Local management is hard to improve on,” she said.

The San Luis Valley, along with many other high desert communities, would look markedly different without its acequia. Nestled at the base of the San Juan and Sangre De Cristo mountains, this region is the driest in Colorado, receiving only seven inches of rain annually.

Youth interns from the Move Mountains Project harvesting corn in Colorado’s San Luis Valley. (Photo courtesy of the Move Mountains Project)

In an acequia community, land-based ecological knowledge is passed down through generations along with time-tested practices such as companion cropping, crop rotation, seed-saving, fire ecology, and agroforestry. “Literally all the tenets of regenerative agriculture that were here well before anyone was talking about it,” Peña said. Many of these practices originated with Indigenous farmers.

Sustainable acequia irrigation regenerates the soil horizon, bringing mineral and sediment-rich water from the mountains to the fields. While acequias remain the primary irrigator in northern and central New Mexico, small-scale farming has declined in the region through massive economic restructuring, depopulation of rural areas, and the move from diversified crops to monocultures.

Today, few farmers grow food in the region. “We’ve become an alfalfa monoculture and beef export colony,” said Peña. “We need to transform farming back to polyculture.”

For Peña, local water management improves soil and crops. But it also means self-determination when it comes to healthy food. On the Acequia Institute’s 181-acre farm, Peña and others are reviving traditional farming practices and crops such as heirloom corn, beans, and squash.

Heirloom varieties of corn grown as part of the acequia system. (Photo courtesy of the Move Mountains Project)

The institute also provides no-interest loans to acequia farmers who are paid by the acre instead of by yield. Farmers have access to youth interns through the Move Mountains Project, aimed at creating “the next generation of farmers,” Peña said.

In 2022, the Acequia Institute purchased R&R Market, the oldest grocery store in Colorado, which was going to close. The institute is converting the space into a worker-led community co-op, a place to distribute the bounty of the acequia system.

The market, now renamed The San Luis Peoples Market, will reopen in late April and include a grocer, deli, commercial kitchen, community center, and market featuring produce from acequia farmers in the valley. In the years to come, Peña plans to open a second commercial kitchen, a USDA-certified slaughterhouse, and a solar-powered greenhouse.

“I know we’re going to bring healthy food and nutrition to the community,” Peña said, as the storm clouds above Culebra Peak cleared. “The model is, we don’t want to go outside the valley.”

July 30, 2025

From Oklahoma to D.C., a food activist works to ensure that communities can protect their food systems and their future.

Like the story?

Join the conversation.