The Southern Farmers Financial Association, years in the making, could be a lifeline for Black farmers and rural communities, but is in jeopardy now.

The Southern Farmers Financial Association, years in the making, could be a lifeline for Black farmers and rural communities, but is in jeopardy now.

March 14, 2025

National Black Growers Council Board member Willis Nelson of Nelson & Sons Farm stands in a field of row crops. (Photo credit: National Black Growers Council)

In 2016, Willis Nelson and his three brothers—third-generation Black farmers—started a farming venture with 40 acres in rural Sondheimer, Louisiana. Located on the western bank of the Mississippi River, the family farm now spans roughly 4,000 acres and produces corn, cotton, soybeans, wheat, and milo.

Expand your understanding of food systems as a Civil Eats member. Enjoy unlimited access to our groundbreaking reporting, engage with experts, and connect with a community of changemakers.

Already a member?

Login

Getting to this current size wasn’t easy, however. In their first attempt to scale up and acquire 640 acres, the brothers turned to the Farm Service Agency (FSA), a loan-making entity of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).

“When we got to the FSA, it was just bad,” says Nelson. “It seemed like they were looking for any reason not to give us a loan.” Nelson and his brothers were repeatedly told that the farm’s paperwork was incorrect and asked to produce what they say was an unnecessary amount of financial documentation.

Despite having a signed contract with the USDA and an agreed-upon work plan, the bank’s launch is now on pause alongside many other USDA programs as they each await review.

“We couldn’t even get a guaranteed loan from other banks, because they kept saying we didn’t have enough cash flow,” says Nelson. This continued for four years until Nelson and his brothers were approached by First Southern Bank after their farm got a writeup in The Christian Science Monitor. The community-oriented bank gave the Nelson brothers their first loan to fully fund their farming venture.

A new effort seeks to jumpstart and sustain small farmers and other agricultural-based businesses in the southeastern United States. The Southern Farmers Financial Association (SFFA) is a cooperative, mission-driven bank designed to lower the barriers to accessing credit for small farmers, especially those in high-poverty and low-resource areas. Historically, limited-resource farmers, often Black farmers and farmers of color, have faced systemic barriers and discriminatory practices when seeking financial support from traditional lending institutions, including governmental agencies.

“This [bank] is about making sure that agriculture works for all and that our rural communities survive,” says Cornelius Blanding, executive director of the Federation of Southern Cooperatives/Land Assistance Fund, a nonprofit organization that supports Black farmers, landowners, and cooperatives with various land retention and advocacy efforts across the South. As the leading partner of the SFFA, the Federation will help the new bank build upon its existing infrastructure across the region and support it with its outreach, education, and technical assistance.

The Biden-Harris Administration’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) provided the SFFA effort with $20 million in initial funding to be dispersed through the USDA—and the bank has had plans to open its doors towards the end of the first quarter of 2025. However, with the Trump administration’s sweeping executive orders and recent crackdown on alleged “radical and wasteful programs,” as well as programs related to diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility (DEIA) and climate change, things are now uncertain.

“While we hadn’t used that language around the bank and don’t consider it to be DEIA, we’re in jeopardy for being labeled as such because of their way of looking at this,” Blanding says. Despite having a signed contract with the USDA and an agreed-upon work plan, the bank’s launch is now on pause alongside many other USDA programs as they each await review.

After review, the SFFA will either be modified to fit new guidelines or completely terminated.

“We’re hoping for the best case and that it will be some kind of modification,” says Blanding.

Farmers of color have long encountered discrimination at the hands of the USDA. They have been consistently denied small loans and access to grant programs, subsidy payments, and other assistance the agency would typically guarantee, resulting in substantial economic losses. The Pigford v. Glickman class-action lawsuit, filed by Black farmer Timothy Pigford against the USDA in 1999, was the culmination of years of discrimination.

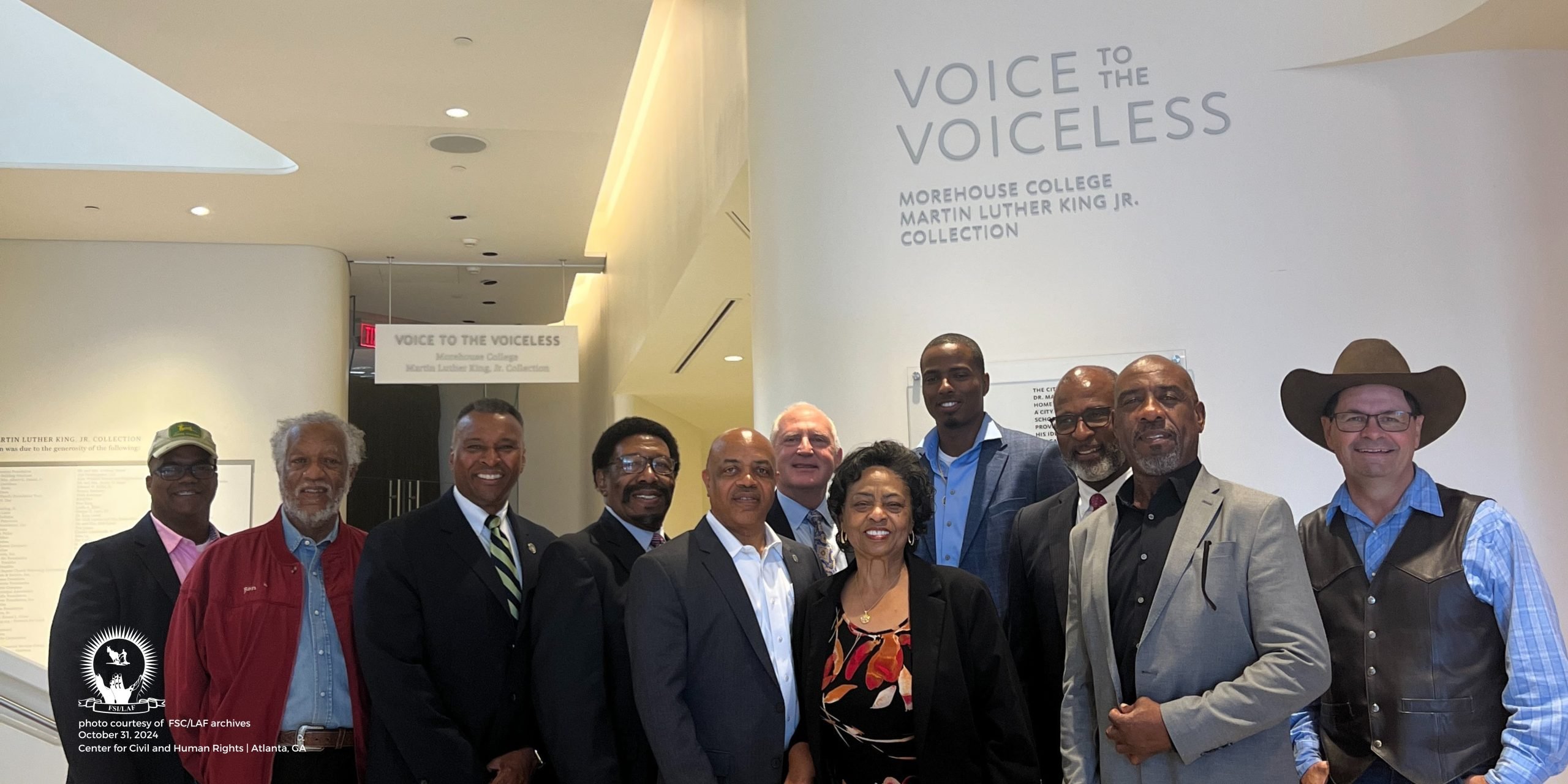

SFFA leaders gather for the press conference launch of the green bank in late October of 2024. (Photo credit: Federation for Southern Cooperatives/Land Assistance Fund Archives)

The concept of a mission-driven—or green—bank started over a decade ago after an informal convening of farmers in Atlanta, Georgia. “Many of the folks who were a part of that convening had been working on the Black farmer lawsuit since 1999, and it was the center of those conversations,” Blanding says.

Those involved in the convening realized that access to credit—which provides the startup capital that most farmers seek to purchase supplies, seeds, and technology—continued to be one of the most significant barriers to low-resource farmers in the region. As a result, they formed committees and dedicated working groups where, eventually, the idea of a cooperative green bank took root.

“When you look at the data, the majority of Black farmers, the majority of low-resource farmers, [and] a majority of farmers of color are located in the Southeast,” Blanding says. This disparity was a significant factor in the decision to base the SFFA in the Southeast region. Headquartered in Atlanta, Georgia, the bank will serve Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas with virtual hubs.

What sets this bank—intended for farmers, landowners, and agriculture-based businesses—apart from a standard bank is its strict focus on agriculture and strengthening rural communities. In the eyes of many traditional lending institutions, a low-resource farm may not be bankable. The SFFA will have a different approach to collateral.

“It’s not about tying up the assets of a farmer or landowner to the point where they can’t survive or don’t have other options,” says Blanding. “It’s about getting to ‘yes’ and working with folks from where they are.”

In partnership with community-based organizations, the SFFA is designed to figure out alternative ways to get those who own land, farm, or run other ag-based enterprises to the point where they are financially viable. The bank is intended to serve as a revolving loan fund that offers reasonable interest rates—and will ideally grow to have assets, enabling it to continue providing financial resources to a farm long after its initial disbursement.

While it is not a grant-making institution, Blanding sees the cooperative green bank as having multiple arms that can have grant-type resources and provide gap financing—a short-term loan or credit line that covers the difference needed for an immediate financial obligation.

To help ensure it remains aligned with the needs and priorities of the farming communities it serves, the SFFA also plans to have various classes of membership for its borrowers. As in a traditional cooperative, members will get a share of earnings and will receive dividends.

Class A membership will give member-owners the highest voting power and the ability to invest more significant sums of money in the cooperative, explains Ben Burkett, longtime farm advocate and the Federation’s Mississippi state coordinator, who, alongside Blanding, was a part of the initial conversations that conceptualized the SFFA. Class B and C cooperative members can invest some capital but have limited to no voting rights.

For low-resource farmers and others in the Southeast, the SFFA would be a safety net that has never existed before. “There are many community-based organizations doing a lot of work with Black farmers and socially disadvantaged farmers,” Blanding says. “This [green bank] is not intended to replicate any of that, but to step in the middle and provide things there weren’t available until now.”

Though its future is uncertain, Blanding believes that the SFFA would be another step in the right direction for justice.

The Pigford lawsuit eventually led to the most robust civil rights settlement in U.S. history, totaling just over $1 billion. However, payouts did not begin for another 15 years, and were only partial. In 2023, the USDA launched the Discrimination Financial Assistance Program and a year later issued payouts to farmers, ranchers, and landowners who had experienced discrimination. “It doesn’t repair what happened historically, but it acknowledges it,” Blanding says.

“When you look at the data, the majority of Black farmers, the majority of low-resource farmers, [and] a majority of farmers of color are located in the Southeast.”

Despite this progress, discrimination remains. Even as recently as 2022, Black farmers had the highest USDA loan rejection rate of any demographic group: 36 percent of Black farmers who applied were approved for direct loans, compared to 72 percent of white farmers, according to an analysis by National Public Radio.

And while Burkett has been a successful farmer for decades, he still experiences the bias that lending institutions hold toward Black farmers. Last year, for example, Burkett financed a tractor with a cooperative credit institution that Burkett has been a member of for over 30 years.

“They took that tractor for collateral, and then they took another one of my tractors and a piece of my equipment,” Burkett says.

The SFFA aims to address the patterns of injustice by, most importantly, acknowledging the historic hurdles low-resource farmers and farmers of color have faced. “No farmer would be discriminated against at this bank, no matter the situation he or she is coming from,” says Blanding. Secondly, farmers have faced injustices simply based on their lack of access to credit. That is the specific problem that the bank is trying to solve.

“We think we can reverse those patterns by addressing those two issues,” says Blanding.

Nelson, whose farm is in the northeast corner of Louisiana, sees a desperate need for the SFFA’s reinvestment in smaller operations. Small farmers near him have faced many problems in recent years, such as climate-change impacts, land loss, and being denied financial assistance.

Willis Nelson and son Wil’laddyn Nelson standing in a soybean field on the Nelson & Sons Farm. (Photo credit: Willis Nelson)

“I’ve been seeing with all the farmers that there is difficulty in making their cash flow,” says Nelson, who is also a current member of the Federation and a board member of the National Black Growers Council. “It’s been a rough four years for the Southeast.”

Considering the high cost of starting and scaling farming operations, many farmers never see investment returns, says Blanding. And farms that are smaller in acreage are more vulnerable to a number of issues that can quickly become financially burdensome.

Climate change—specifically extreme drought and floods—causes many issues for small farmers in particular. With the more intense heat, drought, and storms brought on by the changing climate, “It’s not the original growing seasons that we’re used to,” Nelson says. His farm has been working to keep its yields up and keep up with inflation.

Lenders often want to see the farm’s profitability alongside other factors such as income, credit score, and business plan. Because of the extreme weather, farmers with smaller operations suffer more substantial losses than larger farmers—making it more challenging to get the capital they need to stay afloat.

Alongside climate change, the changing demographics of the farming community creates another challenge. “Some of us [farmers of color] are still losing land,” Nelson says. Additionally, most land in the area is passed down through succession, from one generation to the next, but the youth no longer have as much interest in farming or they lack the resources to start. In many places, people have sold their land or private entities have taken it over. “It’s not family farming anymore,” Nelson says.

“Agriculture is a huge and important part of what this country is. The more people who are part of it and succeeding in it, the better off we are as a nation.”

Burkett also sees medium-size farming operations, or those with gross sales between $100,000 and $400,000 annually, facing outsize problems. “Mid-size farmers—what I call true family farms—are totally being squeezed out” as many farms in the area have had to cease operations or downsize, he says. Farms can either get really big or stay small, says Burkett.

“It just costs so much to do business now with the cost of equipment, labor, industry requirements, safety, rules and regulations,” Burkett says. “You’ve got to have a full-time man or woman just to keep up with those targets.”

Nelson believes a cooperative green bank could help family farmers navigate challenges like these. On his farm, a bank loan would help him carry out certain upgrades, such as installing underground irrigation to prepare for drought.

In the absence of a bank like the SFFA, Nelson had to go through the USDA’s cost share program, known as the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP), to get the equipment he needed to drain the water from his land after a recent flood. The program covered 70 percent of the cost, but Nelson still had to put up 30 percent, impacting other farm needs. And while programs like EQIP are helpful, the funding is limited, not guaranteed, and can require a lengthy wait.

Additionally, some EQIP funding has been paused since the start of the new administration while the USDA conducts a review of grant contracts to determine if they align with President Trump’s executive orders rolling back climate projects and work that prioritizes equity or diversity. While a court ordered the funds to be unfrozen, the agency has only released small batches of that money.

EQIP was one of several programs that got a bump in funding from the Biden-era Inflation Reduction Act for farm projects that prioritized climate goals, so some farmers’ contracts may also be at risk of cancellation. As funding through EQIP and the vast suite of farm programs the USDA runs becomes more uncertain, SFFA could become an even more vital resource—assuming it continues.

Nelson sees the SFFA as a key to rebuilding the farming community from the ground up. With backing from the green bank, reinvestment can look like community-led gardens and agricultural programs that lower the entry point for new farmers. This could mean enabling new or existing small farms to acquire small amounts of acreage, helping them become financially viable and putting them in a position to scale up.

“We [farmers in the area] don’t have to have 1,000 acres to start [farming]—we can get back to the 40- or 100- acre farms, and the rest will follow,” Nelson says.

Nelson believes a localized lending institution like the SFFA would be an enormous first step in rebuilding the assets of farming communities like his across the Southeast. Alongside the lending, Nelson wants to see the cooperative green bank offer financial workshops to teach farmers how to fill out balance sheets, create basic budgets, and manage profit and loss—all skills critical to their survival.

“I’m willing to give my time because we have to make something out of this,” Nelson says.

Late last year, the first portion of the IRA funds were released—just over a million dollars. These funds have already been used to hire a permanent CEO and set up the bank’s infrastructure. Now, the bank founders are waiting to hear from the USDA to learn if and when they will receive the rest of the funding needed to move forward and whether the program will be modified—or, worst case, terminated.

In the meantime, they have been in conversation with aligned organizations like the Native American Financial Services and entities that work with low-resource farmers, such as the Farm Credit System, to spread the word across the Southeast to make sure that farm-adjacent people fully understand what the cooperative green bank offers, and that they can trust it.

The response to the forthcoming cooperative green bank has been overwhelmingly positive. The main question that Blanding and SFFA leadership have heard over the past few months is, “When will it open?”

Since the SFFA’s initial conceptualization, the Federation for Southern Cooperatives has kept its membership abreast and in touch with people inside and outside their farming community.

“Agriculture is a huge and important part of what this country is,” Blanding says. “The more people who are part of it and succeeding in it, the better off we are as a nation.”

July 30, 2025

From Oklahoma to D.C., a food activist works to ensure that communities can protect their food systems and their future.

Like the story?

Join the conversation.