The small blob-like creatures are wreaking havoc on coastal aquaculture—and climate change is making the problem worse.

The small blob-like creatures are wreaking havoc on coastal aquaculture—and climate change is making the problem worse.

May 27, 2025

A lobster fisherman in Maine, where invasive sea squirts are infesting cages. (Photo credit: Peter dennen, Getty Images)

In the summer of 2020, Alicia Gaiero began to realize that sea squirts were putting the success of her new oyster farm in jeopardy. She and her two sisters, Amy and Chelsea, were working together to fulfill their dream of a family aquaculture business, Nauti Sisters Sea Farm, in Yarmouth, Maine.

Expand your understanding of food systems as a Civil Eats member. Enjoy unlimited access to our groundbreaking reporting, engage with experts, and connect with a community of changemakers.

Already a member?

Login

But the critical work of flipping oyster cages—turning them over to combat biofouling and introduce sunlight and air to the bottom—had become impossible. They couldn’t even lift some of them, even though they were made of hollow plastic mesh.

In large numbers, sea squirts—some as large as a pair of tube socks, some smaller than a pinky ring—are surprisingly heavy, and are impacting lobster, oyster, and other fisheries.

The cages were covered and also filled with the globby bodies of sea squirts, invasive marine invertebrates that thrive in the warming waters of the Gulf of Maine and along the coasts of Alaska and the western United States. In large numbers, sea squirts—some as large as a pair of tube socks, some smaller than a pinky ring—are surprisingly heavy, and are impacting lobster, oyster, and other fisheries.

Gaiero had heard that sea squirts could be challenging, but this was out of control. “I’d never seen anything like it,” she says.

By the next season, she felt overwhelmed. “This was ruining my life.”

There are now over 150 independently owned oyster farms in Maine, in part thanks to investment by the state. Under the glistening, still surface of the water, nearly every line and buoy marking a trap or cage is encased with gooey sea squirts—formally known as tunicates, for the tunic-like sheath of fleshy cellulose that covers their siphons, which suck in and filter sea water. The nickname “sea squirts” comes from the fact that they often squirt water when they’re disturbed.

Tunicates, commonly known as sea squirts, are a problem for commercial shellfish farmers, as they glom onto cages and the shellfish themselves. Here, tunicates cover an oyster cage in Casco Bay in Maine. (Photo credit: Alicia Gaiero/Nauti Sisters Sea Farm)

For more than 500 million years, tunicates have existed as simple creatures clinging to underwater substrates and filter feeding on plankton and bacteria. There are hundreds of subspecies. Some have inhabited the Gulf of Maine since the 1800s, arriving in the ballast waters of ships from distant seas; new subspecies have come from Europe and Asia in oyster seed and on cruise ships.

As tunicates spread across oyster cages, mooring lines, and buoys, they add incredible weight, turning a 5-pound oyster cage into an unmanageable 100-pound obstacle. As they proliferate, they compete with bivalves—oysters, mussels, and scallops—for resources and can eventually choke them out entirely. A bivalve covered in globby tunicates can no longer open its shell to feed, and will eventually starve to death.

They were only a mild nuisance to Maine’s working waterfronts until the past decade, when their populations started to soar.

“The biggest thing driving this invasion,” explains Jeremy Miller, research associate and coordinator of the System Wide Monitoring Program at Wells Reserve, “is the warming Gulf of Maine. The Gulf of Maine is getting warmer and warmer every year. Ever since about 2012, we have been going in one direction, and we haven’t had an anomalously cool year since 2007.” According to the Gulf of Maine Research Institute, sea surface temperatures in the gulf have been steadily rising at an average of 0.84° F annually, roughly three times that of the world’s oceans.

The Wells Reserve team researches and tracks changes to the environment along the Wells Estuarine Research Reserve, monitoring changes year on year and sharing their findings with the broader scientific community. (Although they are concerned about potential federal cuts to their overall funding, their studies on invasive species receives private foundation money.) The warming waters have had profound impacts on Maine’s fisheries and waterfronts, from the disappearance of Northern shrimp to more frequent flooding events, including so-called “blue sky flooding” in the coastal city of Portland. And those rising temperatures are now driving a sea squirt population boom.

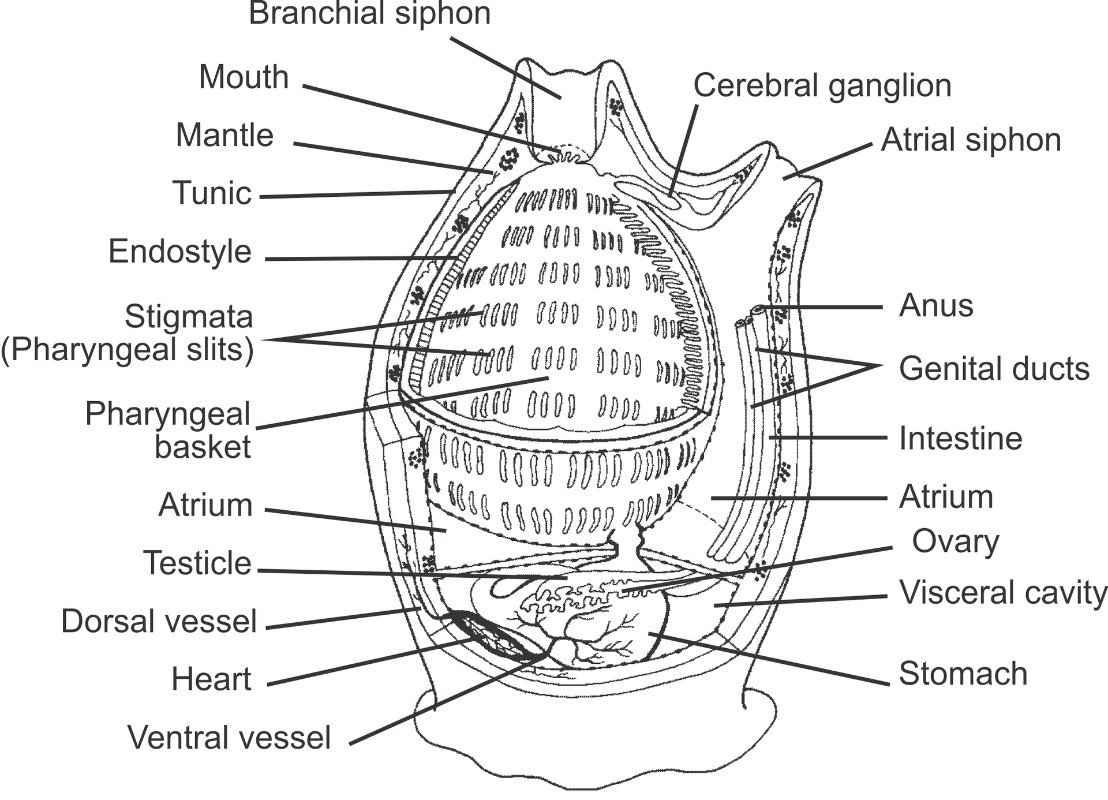

Internal anatomy of a tunicate (Urochordata). Adapted, with permission, from an outline drawing available on BIODIDAC.

Tunicates thrive and spread faster with warmer ocean temperatures. And the rising number of aquaculture farms are providing plentiful structures to which sea squirts can attach themselves and grow.

And there are other factors as well. “The Gulf of Maine, compared to a lot of other parts of the world, is actually fairly low in diversity,” says Larry Harris, Professor Emeritus of Biology Sciences at the University of New Hampshire and co-author of UNH studies on tunicates and warming ocean temperatures. Harris explains that development along the coast of Maine has created the perfect ecosystem for tunicates, with new docks and moorings offering an abundance of substrates for them to attach to in addition to aquaculture farms. Also, tunicates have few true predators in the Gulf of Maine, and overfishing has reduced the number.

Because tunicates are effective filter feeders that grow extremely quickly, they can reproduce alarmingly fast; certain species can double their populations in as little as 8 hours. Some species are considered “colonial,” growing in a super-organism, like coral. Others are called “solitary,” but often appear in clusters and groups because their offspring do not travel far.

And they are not easy to destroy. Cutting a tunicate off a line and throwing it back into the sea doesn’t kill it; a new tunicate will grow from the dismembered piece.

Instead, aquaculture farmers and lobstermen are encouraged to deal with tunicates by desiccation: hauling out traps, lines, and buoys and leaving them in the sun until they fully dry out, which kills the sea squirts. For oyster farmers, combating tunicates means regularly flipping, or “tumbling” the oyster cages to expose the tunicates to the sun.

The Gulf of Maine has a particularly intense tunicate infestation because it’s heating faster than other bodies of water.

The impact of tunicates extends beyond oyster farms. As part of his work at the Wells Reserve, Jeremy Miller manages the Marine Invader Monitoring and Information Collaborative. Traveling to different working waterfronts and Maine islands, he’s found lobstermen complaining about tunicates covering their traps, and hears of mussel farmers whose lines have snapped from the sheer weight of the tunicate blobs. Moreover, the diet of a tunicate—nutrients filtered from seawater—is similar to that of shellfish, reducing resources for native filter feeders.

“People are kind of shocked at the amount of actual biomass of these things,” Miller says. “From a biological standpoint, these are taking nutrients—it takes a lot of stuff to grow that biomass, and it’s all stuff that other things could be using. That creates a big impact on aquaculture.”

The Gulf of Maine has a particularly intense tunicate infestation because it’s heating faster than other bodies of water. But global ocean temperatures are all rising, and tunicates have become a nearly worldwide problem. Three species have appeared in the Puget Sound area of Washington State. Invasive tunicates have even been discovered in the waters off Sitka, Alaska.

A few radical solutions to the tunicate invasion are in the works. A Norwegian company, Pronofa ASA, has perfected a method for turning the meat of the sea squirt genus Ciona, now common in Maine, into mincemeat for human consumption, much like ground beef.

While not all tunicates are edible, many of the varieties currently invading Maine’s coast are, including clubbed tunicate and members of the Ciona species. Tunicate meat is slightly chewy, reminiscent of calamari. Wild tunicate does look unappetizing, however. The fleshy tubes growing in Maine’s waters are brownish, barrel shaped, and flaccid.

A display of sea pineapples (hoya, known as 海鞘 and 老海鼠in Japanese) at a market. These sea creatures are a delicacy in Japanese cuisine, prized for their unique texture and oceanic flavor, and are often served in sashimi or other traditional dishes. (Photo credit: DigiPub, Getty Images)

It can be a struggle to convince consumers to eat these creatures. But in some parts of the world, they’re a welcome food.

“In Asia, they eat the club tunicate,” explains Larry Harris, University of New Hampshire Professor of Biological Science. “They peel off the outer coating. And in Australia they are a pretty standard part of some diets.” In Chile, a rock-like variety called piure is being embraced by fine-dining establishments as a sustainable and local seafood option.

In Norway, the sea squirts for Pronofa’s culinary experiment are farmed, an idea that causes alarm for Maine farmers as it would mean purposefully introducing tunicates to the environment. It remains to be seen whether intrepid chefs may start experimenting with wild-harvested tunicates. In other parts of the world, including Chile, Argentina, and the Mediterranean, sea squirts are part of the local diet. They are easy to harvest and prepare on any waterfront, and recipes for sea squirts abound in these places.

Even if Americans don’t eat them, sea squirts can be transformed into high-protein feed for various animals, from chickens to salmon, and some have begun exploring that possibility.

University of New Hampshire professor Harris began experimenting with tunicates for animal feed decades ago. But he discovered that a Norwegian company, Ocean Bergen, already held a patent for that purpose, which extended to the U.S., so he discontinued his efforts. Ocean Bergen is one of a handful of Norwegian companies working with tunicates as a future food-system solution. Researchers believe that Ciona, which thrives in the freezing waters around Norway, could help clean the water around salmon farms, filtering out the excess nutrients that cause harmful algal blooms.

Two varieties of tunicate that are taking over Maine waters. (Photo courtesy of the Wells Estuarine Reserve)

Scientists are also experimenting with using tunicates for biofuels. Because they produce cellulose to make their outer tunic bodies, tunicates can be broken down to produce ethanol. Since initial studies in 2013, tunicates have been suggested as a potential fuel of the future, but progress with these experiments has been slow and heavily regulated.

Using tunicates for animal food or biofuels would also involve cultivating them for a reliable harvest, which would meet resistance from the aquaculture industry. Since sea squirts are already wreaking havoc on the seafront, a tunicate farm would likely not be welcome near any existing oyster, mussel, or scallop aquaculture operation.

It may be a while before Mainers consider the idea of eating a sea squirt. Meanwhile, the most important step in preventing tunicate spread is effectively stopping their proliferation. As ocean waters continue to warm, and Maine’s aquaculture industry continues to grow, it is likely that the sea squirt will thrive, and aqua-farmers will have to deal with them.

As Larry Harris warns, “Every dock, every net, is a potential population.”

July 30, 2025

From Oklahoma to D.C., a food activist works to ensure that communities can protect their food systems and their future.

Leave a Comment