Artist and activist jackie sumell’s nonprofit, Freedom to Grow, takes a plant-powered approach to encourage radical change.

Artist and activist jackie sumell’s nonprofit, Freedom to Grow, takes a plant-powered approach to encourage radical change.

June 18, 2025

Established last October, the final Solitary Garden is on St. Charles Avenue, a popular tourist destination in New Orleans. (Photo credit: Ben Seal)

St. Charles Avenue, the regal boulevard at the center of New Orleans, is a beacon of wealth and comfort in a city where both are hard to come by. Antebellum mansions and stately oaks line the avenue, which winds through the pristine campuses of Loyola and Tulane universities. Here, in the historical center of the American slave trade, affluence is the norm, even as nearly one-quarter of the city lives in poverty.

Expand your understanding of food systems as a Civil Eats member. Enjoy unlimited access to our groundbreaking reporting, engage with experts, and connect with a community of changemakers.

Already a member?

Login

On a block sandwiched between the college campuses, a 6-by-9-foot garden bed on the front lawn of the St. Charles Avenue Baptist Church challenges the neighborhood’s image.

The garden’s dimensions replicate those of a standard solitary confinement cell.

Within the garden, the outline of a prison bed, sink, and toilet is filled with “revolutionary mortar,” a mix of clay, lime, and ground cotton, sugarcane, and tobacco—the crops central to chattel slavery. Plants can grow only in the negative space around those features, further restricting the garden’s capacity and imparting a sense of claustrophobia. Facing the street, an aluminum gate stands tall to represent a cell door. Thankfully for the plants, this one lets sunlight pass through.

What the Garden Grows—and Shows

The garden urges passersby to consider mass incarceration as an evolution of enslavement. It is a Solitary Garden, one of more than two dozen built in the past decade in New Orleans and beyond—from Philadelphia, New York, and Houston to the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center in Connecticut. Behind all of them is the artist and activist jackie sumell and her compatriots at Freedom to Grow, a nonprofit incorporated last year that’s dedicated to abolishing prisons. Each garden is designed by an incarcerated person—with a collection of flowers, herbs, and vegetables grown for them until they can grow again themselves.

“The point of prisons is to tuck people away, out of sight, in rural areas where nobody will think about them,” says Rev. Marc Boswell, the church’s pastor. “The garden humanizes and brings to mind people who are incarcerated, what their hopes and dreams are, and that they have hopes and dreams.”

Church congregants suggested the idea for the St. Charles garden and have found joy in its symbolic display, Boswell says. It was installed last fall with contents chosen by Obie Weathers, a man on death row in Texas who asked that it resemble the family garden he grew up with.

A self-taught artist and poet, Weathers has spent 25 years in solitary confinement, sentenced for murder when he was a teenager. In mid-April, his garden boasted cabbage, kale, cucumbers, and radishes, as well as aloe that survived a rare winter frost.

Cedar Annenkovna, left, and jackie sumell harvest vegetables and flowers from a Solitary Garden in the Ninth Ward. (Photo credit: Ben Seal)

“We don’t just plant islands—we plant a community of diverse plants that support each other,” says Cedar Annenkovna, Freedom to Grow’s lead garden steward, as she picks a leaf of kale. Reflective and compassionate, Annenkovna designed her own Solitary Garden for two years while incarcerated, then moved to New Orleans upon her release last year to tend the gardens herself.

The garden is an invitation to consider abolition—and it is also a reflection of beliefs that permeate all of Freedom to Grow’s work: that plants, through their patience, persistence, and interdependence, can teach us to be better people.

In a society hardened by antiquated values, sumell says, abolition often makes people feel fearful or apprehensive. But she believes the natural world possesses a superpower that opens the door for people. After all, what is a garden if not a study in ceaseless change?

The gardeners themselves undergo change, too. Speaking by phone from Angola prison, Kenny “Zulu” Whitmore describes the power of planting a garden from inside. When he designed his own, at a site in the Ninth Ward that holds several Solitary Gardens, the prison had just eradicated all of its stray cats, so he asked that the garden be filled with catnip to ease the anxiety of any passing felines. Whitmore has spent 49 years incarcerated for second-degree murder, including 28 in solitary, and the garden was profoundly restorative: “It reconnected me to who I really am.”

‘Seduce and Destroy’

For sumell, a bundle of dark curls and restless energy who doesn’t capitalize her name, the Solitary Gardens are a rebuke of the ways that agriculture is weaponized within prisons. A provision of the Thirteenth Amendment, which banned slavery, allows the state to force labor on the incarcerated. In most states, that labor includes working with crops and on farms for pennies, if they’re paid at all.

The gardens are part of her mission to “seduce and destroy.” This entails introducing those wary of abolition to its foundational principles by way of a garden in bloom—and then encouraging them to “imagine a landscape without prisons,” as inscribed on the frame of the garden beds.

“I’m talking about destroying ignorance and complicity and our inurement to punishment—our ignorance around the belief that the only way we can respond to harm is through punitive mechanisms,” sumell says. “Plants represent an antidote to that in the ways that they are generative and grow together and create their own communities.”

The incarcerated gardeners typically approach Freedom to Grow after hearing about its work and wanting a garden of their own. Occasionally, recommendations come from like-minded initiatives like Solitary Watch, a nonprofit newsroom focused on harsh prison conditions, or Nicole Fleetwood’s Marking Time, a contemporary art exhibition exploring the impact of the prison system.

Although all gardeners have spent time in solitary confinement, that’s not a requirement for participation in the project. Through written correspondence, they share sketches of the gardens they’d like to see planted, and Freedom to Grow’s staff and supporters share pictures as they evolve. While Annenkovna manages most of the gardens, a few are tended by committed volunteers.

When the St. Charles garden was established last October, supporters and neighbors stopped by to offer support. In the months since, many more have paused to engage with its message, according to Caroline Durham, who has helped tend the garden through her work at the Center for Faith + Action.

A former public defender who grew up in the neighborhood, Durham spent years condemning the harms of solitary confinement. “But to see not just the exterior but the internal space has been really powerful,” she says, balanced by “the fun and the joy of having my hands in the soil.”

“I’m talking about destroying ignorance and complicity and our inurement to punishment.”

The St. Charles garden was completed almost 10 years after sumell began the Solitary Gardens project, and she decided it would be her last. The concept is open source and has already been picked up by others, like Planting Justice, a farm in Oakland, California, that employs formerly incarcerated people and is creating three Solitary Gardens of its own.

Given St. Charles’ prominent place in the city’s history, sumell says, “building a prison cell-turned-garden-bed out of sugarcane, cotton, and tobacco, where all of this confluence of fucking wealth from those crops exists, on a corner, just out in the open, is an appropriate bookend.”

The Seed of the Solitary Gardens

In a shaded oasis in the sun-drenched Seventh Ward, sumell tells the story of the garden that started it all.

In 2001, while living in San Francisco, where she’d received a master of fine arts degree from Stanford University, she met Robert King, who had been recently released from prison. King was one of the Angola Three, a trio of Black Panthers who were targeted for political activism while in Louisiana’s notorious state penitentiary in Angola, a former plantation site. The men spent a collective 114 years in solitary confinement.

Inspired to join a movement to free the other two men, Albert Woodfox and Herman Wallace, sumell moved to New Orleans to help organize. In letters, she asked Wallace to describe the house of his dreams. His vision, filled with cut flowers in vases and gardens that could feed hungry kids, informed “The House That Herman Built,” their joint art exhibition that brought the house to life—and brought visitors into the mind of a man kept 23 hours a day in a room narrower than his wingspan.

Wallace was released on October 1, 2013, when a federal judge ruled his indictment for killing a prison guard was unconstitutional. sumell calls his return home the greatest day of her life, though Wallace died of cancer just three days later.

The following year, sumell created the first Solitary Garden here in the Seventh Ward, out of “respect for Herman’s revolutionary commitment to centering plants and gardens, even from within concrete and steel,” sumell says.

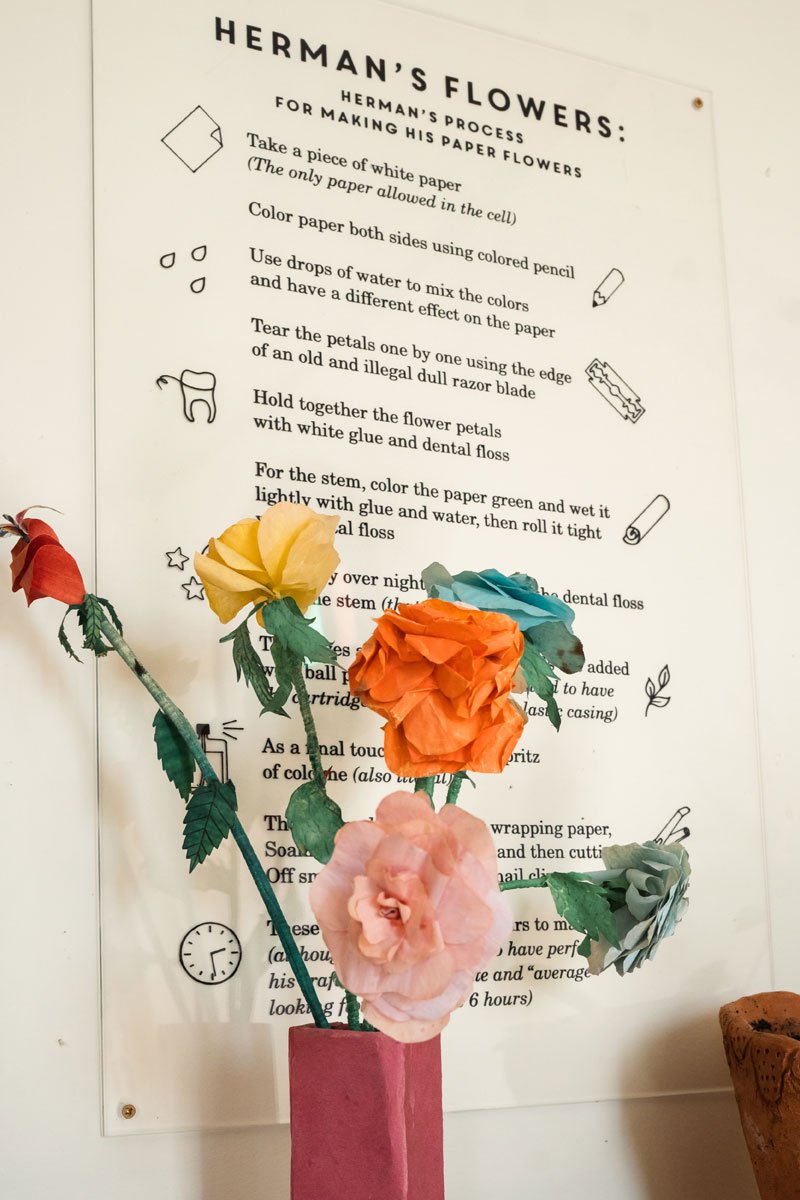

The garden was filled with vegetables selected by Woodfox: squash, corn, and greens. It is still there, but its contents have changed to include a range of herbs. The space around it is now known as the Abolitionist Sanctuary, a place for people to gather and consider the possibilities of abolition. sumell lives next door. Beside her bed, she keeps a bouquet of paper flowers Wallace gave to her the first time they met without a partition between them, during a visit at Angola.

By her bedside, jackie sumell keeps a bouquet of paper flowers given to her by Herman Wallace the first time they met without a partition between them, during a visit to Angola prison. (Photo credit: Ben Seal)

To date, Solitary Gardens have been part of four successful parole packages, sumell says. She sees the gardens as an antidote to the prison industrial complex and systems that support it. It’s fitting that the gardens emerged in Louisiana, which sumell calls “the belly of the beast,” a state whose incarceration rate vastly outpaces the U.S. average.

After years cobbling together artist grants to sustain its work, Freedom to Grow, based on St. Bernard Avenue in the Seventh Ward, is now supported by the Mellon Foundation’s Imagining Freedom initiative, which will fund the operations for three years. In doing so, it will allow the burgeoning nonprofit to expand its work. This work includes a planned archive about abolitionist leaders; the Abolitionist’s Apothecary, which sells wellness products derived from the current gardens; and Liberation Landscaping, a budding effort to plant residential gardens across New Orleans.

Transforming Pain Into Medicine: The Abolitionist’s Apothecary

In the Lower Ninth Ward, a section of New Orleans devastated by Hurricane Katrina and still struggling to recover, sumell and Annenkovna harvest calendula, an anti-inflammatory, and nasturtium, a disinfectant, from several Solitary Gardens in various stages of decay. Unlike the materials that build a prison, the “revolutionary mortar” used in these garden beds is designed to break down over time, typically beginning about two years after they’re built. When it does, gardeners are asked what they’d like their dissolved cells to become.

For Warren Palmer III, who earned a horticulture degree while incarcerated, the answer was to reshape his garden into the wings of the caduceus, the symbol of medicine—fitting, given that he’s now Freedom to Grow’s apothecary adviser. Today, his garden is filled with skullcap (a sedative), primrose (an antiseptic), chamomile (a calming herb), and a range of other plants that provide medicine, including two types of cotton, which supports menstrual health. Like all Freedom to Grow gardens, small signs teach visitors about a plant’s medicinal qualities and its lessons on abolition. (An online companion offers further education on abolition, prompting visitors to contemplate questions about systems of oppression and cycles of trauma.)

“When you put a seed in the soil, who knows if it’ll flourish or prosper or what will become of it?”

When the plants are harvested, they’re brought to the Abolitionist’s Apothecary, a nook within the John Thompson Legacy Center, where Freedom to Grow is headquartered. The center is named in honor of an organizer who became a criminal justice reform advocate while spending 18 years wrongly incarcerated.

The shelves in the apothecary hold an abundance of dried herbs, leaves, and flowers, as well as bottles and jars of all shapes and sizes holding tinctures, salves, balms, and ointments. Those products will soon be sold in Planting Justice’s pay-what-you-can café in Oakland, as well as through a wellness CSA in New Orleans.

Palmer was incarcerated at 17 for second-degree murder and released 30 years later, in 2021. Like many incarcerated in Angola, nearly three-quarters of whom, like him, are Black, he was forced to pick cotton as part of the prison’s labor program. By inverting the way agriculture is used within prisons, Freedom to Grow is turning a source of pain into one of healing.

For Annenkovna, the pain of incarceration is still fresh. The Colorado Supreme Court overturned her conviction last year after she’d spent six years in prison. For two of those years, she designed her own Solitary Garden, filled with her “seven sisters”—a collection of plants that connects her to her roots in Azerbaijan, each with its own medicinal properties: peppermint for clarity of mind, rue for sinus infections, mullein for respiratory health, garlic to lower blood pressure, dill for pancreatic health, mustard for digestion, and yarrow for healing wounds and menstrual pain. When she first walked into the apothecary, she found her seven sisters, harvested from her Solitary Garden and blended into a tea to help heal those harmed by the criminal legal system.

“I looked up and she was holding the jar,” sumell says, “and I thought, ‘Oh my god, it’s all working.’”

Putting Lawns to Use: Liberation Landscaping

At The First 72+, a transitional home for formerly incarcerated men re-entering society a mile from downtown New Orleans, Annenkovna manages three garden beds planted as a pilot for Liberation Landscaping. Community members who take part will pay to have their lawns transformed into medicinal forests to supply the apothecary and provide jobs for formerly incarcerated people.

This is a heavily symbolic place to launch this project. If Louisiana is the belly of the beast, this is among its darkest chambers. Orleans Parish Prison towers behind the gardens, a reminder of the thousands who were abandoned there without power and food when Katrina hit. The prison never reopened, but another stands nearby, holding 1,500 inmates—well above its capacity—and yet another is being built. In March, Louisiana resumed executions after a 15-year hiatus, making Freedom to Grow’s work all the more urgent, sumell says.

“When you put a seed in the soil, who knows if it’ll flourish or prosper or what will become of it? Who knows of a soul, what will become of it?” Annenkovna says. “But it has the potential to contribute to society and give back and sustain and beautify and support others around it. That’s what plants do, and that’s what humans are also designed to do.”

July 30, 2025

From Oklahoma to D.C., a food activist works to ensure that communities can protect their food systems and their future.

Leave a Comment