Oatman Flats has undergone a dramatic transformation, becoming the Southwest’s first Regenerative Organic Certified farm and a potential source of ideas for weathering climate change.

Oatman Flats has undergone a dramatic transformation, becoming the Southwest’s first Regenerative Organic Certified farm and a potential source of ideas for weathering climate change.

May 12, 2025

Oatman Flats Ranch farm manager Yadi Wang kneels in a field of cover crops, planted during fallow periods to help restore soil health and reduce erosion. (Photo credit: Samuel Gilbert)

A version of this article originally appeared in The Deep Dish, our members-only newsletter. Become a member today and get the next issue directly in your inbox.

Expand your understanding of food systems as a Civil Eats member. Enjoy unlimited access to our groundbreaking reporting, engage with experts, and connect with a community of changemakers.

Already a member?

Login

One mid-morning in May, the temperature at Oatman Flats Ranch, in southern Arizona’s Sonoran Desert, had already soared into the 90s. By 4 p.m., the thermometer peaked at 105 degrees—a withering spring heat, but still mild compared to the blistering summer months ahead.

“I joke that this farm is a little better than Death Valley, but I’m not really joking,” said Yadi Wang, the farm director, as he drove his pickup through this 665-acre ranch about a two-hour drive from Phoenix.

“If we’re going to hold on to farmland, we need a significant change in how we farm and what we farm.”

For Wang, every day at the ranch is different. During the winter, he spends his days preparing fields of heritage wheat, planting seeds, and laying pipes from irrigation ditches to the row crops edging the now-dry Gila River. Early summer is the busiest, with the farm team spending up to 10 straight days harvesting the desert-hardy wheat, barley, and other grains.

“These cash crops translate into the tangible,” Wang said. Yet much of his time is devoted to a longer-term, less noticeable project: restoring degraded land, often through practices that originated with the Indigenous peoples of this region.

Oatman Flats Ranch is attempting to create a sustainable, scalable model for regenerative farming in the Southwest, demonstrating what can and perhaps should be grown in an increasingly hot, dry, and water-limited region. In 2021, Oatman Flats Ranch became the region’s first-ever Regenerative Organic Certified farm, with practices build soil health and biodiversity, help sequester carbon, and reduce water consumption. Now it’s been designated as a Regenerative Organic Learning Center by the Regenerative Organic Alliance (ROC), welcoming other farmers interested in observing and talking about the practices there.

Those time-tested practices will become increasingly important as Arizona farmers grapple with the worst water crisis in the state’s history.

“If we’re going to hold on to farmland, we need a significant change in how we farm and what we farm,” said Dax Hansen, the ranch’s owner.

A combine harvests blue durum wheat on the south side of Oatman Flats Ranch in the summer. (Photo courtesy of Oatman Farms)

But it won’t be easy. Oatman Flats Ranch has undergone a dramatic transformation that required significant investments in training, research, equipment, and techniques, all of which took years to deliver a return. Although processes have been refined and problems worked out along the way, with insights that Hansen freely shares with other farmers, many practices are out of reach for the average farmer.

“It’s an experimental farm,” Wang said. “I have a lot of respect for [Hansen], willing to get all these cash assets to pour into this, to lose money. Not many people can or are willing to do that.”

Hansen, a successful financial technology lawyer who grew up in Mesa, Arizona, purchased the property from his aunt and uncle in late 2018. Oatman Flats Ranch has been in the family for four generations. His grandfather Ray Jud Hansen ran cattle in the 1950s before becoming one of Arizona’s first conventional cotton farmers.

The land was severely degraded when Hansen bought it, with compacted, salty, eroded fields caused by decades of conventional farming practices and 10 years of neglect. The soil was more than 55 percent clay. “It was pretty bleak,” Hansen said. “[The land] had basically been sterilized, with almost nothing growing on it.”

Hansen wanted to demonstrate the potential for regenerative farming in the arid Southwest, so he and his team redesigned the farm. They began by restoring the dilapidated infrastructure, repairing wells and pump equipment, excavating irrigation ditches, and purchasing the necessary farm equipment. They cleared hundreds of invasive trees, leveled the fields, fertilized them with manure, and planted cover crops to improve soil and water quality. In addition, Hansen commissioned an ethnobotany and archaeology study of the property to understand what crops had historically been planted at Oatman Flats Ranch.

Meanwhile, the neighboring farmers no longer grow food for people; their crops provide feed and fuel. Oatman Flats Ranch is surrounded by millions of acres of alfalfa for livestock and corn for ethanol, watered by one of the world’s fastest-draining aquifers.

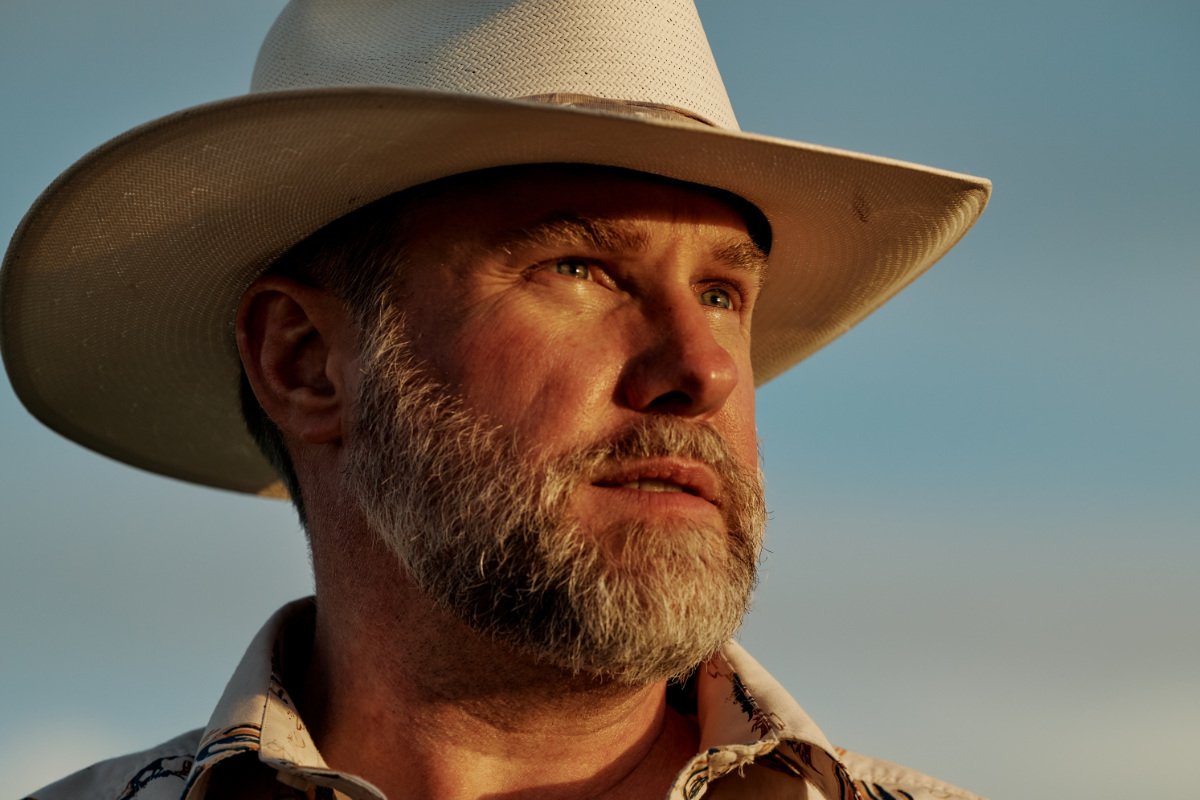

Dax Hansen purchased the farm in 2018 with his wife, Leslie Hansen to create a model of regenerative farming in an increasingly hot and water-scarce Southwest. (Photo credit: Adam Riding)

“Climate change and a persistent megadrought are reducing the flow of rivers in the West, yet we have been unable to sufficiently reduce our dependence on these rivers to keep demands balanced with supplies,” said Brian Richter, president of Sustainable Waters, an organization focused on water scarcity issues. “The result is increasing depletion of rivers, lakes, and aquifers.”

The constraints led Hansen and his wife to explore water-conserving crops. His team planted drought-tolerant, and nutrient-dense White Sonora wheat and mesquite trees.

“We embraced the abundance of heirloom and native crops in the Sonoran Desert,” Hansen said. “We are looking at the land and asking it what we should grow, rather than asking the land to grow what we want.”

Hansen hired farm attendant Juan Carlos Gutierrez and Wang, who shared his vision of healing the land and were knowledgeable about water, soil, and biodiversity. Wang has a bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering and a Ph.D. in agriculture and life sciences. Gutierrez does a bit of everything at the farm, including planting and harvesting, maintaining farm equipment, managing cover crops, rotating animals, and milling wheat and mesquite into flour.

In five years, Oatman Flats Ranch’s regenerative practices saved over a billion gallons of water, doubled the amount of organic matter in the soil, and steadily transformed the once-beleaguered ecosystem, according to its May 2024 Regenerative Impact Report. The water savings are measured by tracking the flow rate of each well on the ranch to calculate the amount of water used per round of irrigation. The acre-feet of water used at Oatman Flats Ranch are then compared to the estimated acre-feet used in conventional wheat production. (One acre-foot is enough water to flood a football field 1 foot deep, or more than 325,000 gallons.)

“When we grow regenerative, we can use 2 or 3 acre-feet of water,” Hansen said. “Alfalfa and cotton will take like 9 or 10 acre-feet.”

To measure soil organic matter, Wang takes samples from the surface of the fields and sends them to the Motzz laboratory in Arizona and the Regen Ag Lab in Nebraska for analysis. Soil organic matter is the key indicator of soil health, influencing nutrient and water availability, biological diversity, and other factors critical in growing healthy crops. In some fields, soil organic matter has grown from 0.8 percent to 2.4 percent, according to the lab results. Yadi said 0.8 percent is about normal for the region, while 2.4 percent is very high, an outlier. “People think it’s impossible,” he said.

Southern Arizona’s rich agricultural history stretches back more than 5,000 years. By 600 CE, the Hohokam people were constructing North America’s largest and most elaborate irrigation systems along the Salt and Gila Rivers. The descendants of the Hohokam—the Pima and Tohono O’odham—continued to farm the land up to and after the arrival of the Spanish, who began to colonize southern Arizona in the 1600s. They continue to farm in Arizona today.

At the Tohono O’odham Indian Reservation, about two hours southeast of Oatman Flats, the San Xavier Co-op Farm uses historic land management practices and grows traditional crops that reflect their respect for the land, plants, animals, elders, and the sacredness of water.

San Xavier Farm Manager Duran Andrews and his team plant cover crops, rotate fields, and collect rainwater. “[Regenerative agriculture] is nothing new to us,” Andrews said. “We have been doing this for decades. Harmony between nature and people has been our approach all the time.” Rotating fields and cultivating multiple mutually beneficial species in the same fields improves water and soil quality and biodiversity in this harsh landscape.

“You’ve seen what the land looks like in five years; imagine it in 10. If we can do it here, we can do it anywhere.”

The co-op grows a variety of native crops that were developed in the region and cultivated for centuries or, in some cases, millennia, such as grains and beans, which they sell online. “We irrigate them till they sprout, then cut them off till the monsoon shows up,” Andrews said. “We try to keep crops in that hardy state through all the years and decades they have been here. We try not to get away from how things were done in the past.” They also grow White Sonora wheat, introduced to Arizona by Spanish Jesuit missionaries in the 1600s. “It was a gift from Father Kino that we have taken as our own,” Andrews said. “The [San Xavier] community was one of the first to grow this wheat.”

Following the Mexican-American War in the mid-1800s, the United States claimed parts of modern-day Arizona, New Mexico, California, Nevada, and Utah. The Anglo ranchers who moved into the area dug canals to irrigate agricultural fields, transforming the landscape. An 1852 watercolor by surveyor Jon Russell Bartlett depicts a verdant valley with cottonwoods and mesquite trees lining a flowing Gila River as it passes through Oatman Flats Ranch.

That landscape is unrecognizable today. The lower Gila has gone bone dry after years of upstream diversions, dams, water overuse, and climate change. In 2019, the Gila River earned the title of Most Endangered River by the nonprofit advocacy group American Rivers.

Standing on the sandy Gila riverbed, which divides the north and south farms of Oatman Flats Ranch, Wang pointed to the nearby invasive salt cedars. Healing the land involves rebuilding the water, nutrient, and carbon cycles from the ground up, “at the micro level,” he said. “On the macro level, it’s broken.”

The ranch team has poured resources into rebuilding soil health by planting hedgerows and 30-plus species of cover crops, at a cost of approximately $100,000. The hedgerows, mostly native trees, were planted along the edges of the fields to reduce erosion and provide habitat for beneficial species, including pollinators such as bees and hummingbirds.

The cover crops—millet, chickpeas, sunflowers, sorghum, sudan grass, broadleaves, and native grasses among them—are planted immediately after harvesting wheat, to provide “soil armor,” help conserve water, fix nitrogen in the soil, suppress weeds, attract beneficial insects, and sequester carbon. The once-barren land now supports life for more than 120 species of flora and fauna.

Farm manager Yadi Wang with a handful of mesquite pods picked from a tree near the farmhouse. The mesquite pods are dried and ground into a gluten-free, nutrient-dense flour. (Photo credit: Samuel Gilbert)

“When you take life away, it just doesn’t come back unless you provide the resources,” said Wang.

The varying heights of the cover crops make multi-storied microclimates, with vapor condensing near the cooler soil surface, creating dew. “I can make dew in the hottest part of July, when the ambient temperature is over 90 degrees by 9 a.m.,” Wang said.

Instead of tilling the cover crops into the fields at the end of their cycle and disturbing soil structure, the team uses a roller-crimper—a ridged cylindrical drum attached to a tractor—to cut stalks and lay the crops down “like a carpet” to protect topsoil, Hansen said. Switching to roller crimping saves money, too, since it costs one-third less than tilling.

The roots remain in the soil, reducing soil erosion and creating an extensive microbial network that cycles nutrients, builds soil organic matter, and increases water infiltration “like a sponge,” Wang said. All of this protects soil from high temperatures, too.

The fields slope ever so gradually to allow irrigation water to move down the rows. In the early years, water would race down the hard-packed dirt, spilling into the Gila drainage. Now, Wang has the opposite problem: When he irrigates, it takes days for water to spread three-quarters down the length of the field. In response, the ranch plans to switch to sprinklers to save water, expand cultivable land, and mimic natural rainfall. The sprinklers are expensive and cost about $1 million, most of that already paid by a water irrigation efficiency grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. This move away from flood irrigation is gaining traction in the parched Southwest.

In 2022, Oatman Flats Ranch introduced sheep, natural lawnmowers that prune back cover crops and weeds while fertilizing the soil. They are rotationally grazed from field to field to give plants in each area a chance to recuperate and strengthen their root systems.

Now, six years after regeneration efforts began, 90 animal species have returned to the area around the farm, including mountain lions, owls, and tiny blue dragonflies—”a sign of water,” Wang said—who weave in and out of rows of White Sonora wheat.

Although Wang and his team are introducing new crops, including native and heirloom melons, their signature crops are mesquite and White Sonora wheat.

Mesquite trees are superbly adapted desert plants. At the ranch, they’re planted in dense groves near the farmhouse. Their taproots can burrow 200 feet deep, and they can shed their small, waxy leaves—designed to conserve moisture—in extreme drought.

Sonora wheat, barley, and other desert-hardy crops stretch along the now-dry Lower Gila River valley at Oatman Flats Ranch. (Photo credit: AJ Ledford)

Their green-bean-like pods were a staple food for Indigenous people in this region, rich in fiber, protein, and calcium. When dried and ground into flour, they have a mildly smoky, nutty, molasses-like flavor. Wang’s wife adds the flour to her coffee, making a frothy, slightly sweet, nutrient-packed latte.

White Sonora wheat is a key part of Hansen’s vision for a regenerative grain economy. The wheat is sown in November or December and harvested in late spring or early summer.

Standing in a field of pale golden wheat stalks, Wang threshed the grain from the chaff by rubbing his palms together as if warming his hands on a cold day. The berries resemble tiny deer hooves, with a groove in each golden-colored grain.

“This is as clean as you can get,” Wang said. “No synthetic fertilizer. No chemicals. Drying on the stalk.” The ranch’s cold-stone milling process preserves the grain’s vitamins and minerals, and retains its naturally sweet, mild flavor.

Oatman Flats Ranch sells Regenerative Organic Certified (ROC) products such as stone-milled flour and mesquite flour, as well as bread, pancake, and waffle mixes, under the Oatman Farms brand. The flours and mixes are now used by numerous restaurants, including Arizona Wilderness Brewing Company.

“We are looking to partner with and help sustain farms like Oatman,” said Jonathan Buford, CEO and brewmaster at Arizona Wilderness, which sources sustainable ingredients from more than 50 local producers. “We need to look at a different currency than just capital. We must consider that Earth must profit, too, for the future of our planet.”

Hansen is sharing what he has learned. Oatman Flats is one of the country’s five Regenerative Organic Learning Centers, which other farmers can visit to observe regenerative solutions that they can potentially put to use on their own farms.

To better understand how the regenerative movement is evolving, Hansen routinely talks to other farmers, and he’s clear about what must happen for it to really take hold. “It is absolutely true that farmers don’t have the resources to do this on their own,” Hansen said. “Farmers need help from consumers, restaurants, and governments to pull off this regenerative effort. I believe we can make regenerative agriculture viable by explaining the plight of the land and the farmers and nature and boldly proclaiming the solution of regenerative agriculture.”

Six years after regeneration efforts began, 90 animal species have returned to the area around the farm, including mountain lions, owls, and tiny blue dragonflies.

The transition to a Regenerative Organic Certified (ROC) model can require a large investment, as it has for Hansen. And it takes three to five years to reap the benefits of regenerative practices, according to Elizabeth Whitlow, founder and senior advisor of the Regenerative Organic Alliance (ROA), which oversees the ROC framework and guidelines.

For most farmers, this is not an option. Margins are thin, and financial constraints often inhibit farmers from exploring regenerative practices. “The only option is to do the cheapest thing you can to survive,” Wang said. “[There is] no room to consider what they could do differently.”

The paybacks of regenerative organic farming can be significant, however. They include reduced costs of inputs such as fertilizers, pesticides, and water, as well as increased profits from high-value products. “I do see brands stepping in and up to provide long-term contracts with farmers while they transition into this new, unknown territory,” Whitlow said. “The premiums and long-term stability offered through this kind of contract agreement help the farmers.”

Besides Hansen’s own funds, Oatman Flats Ranch has also been supported by payments from the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service for on-farm conservation programs, such as tree planting and conservation cover. As the Trump administration cuts climate-related programs, Hansen said Oatman Flats would be affected by “the elimination of Arizona statewide programs supporting local food systems.”

Hansen nonetheless believes that in time, a financially viable model for regenerative organic farming is possible, particularly as demand for ROC products grows. A 2022-2023 impact report from the ROA showed that ROC product sales grew 22 percent on average between 2022 and 2023, reaching nearly $40 million. But profitability, he said, will take “quite a while.”

With the growth of regenerative agriculture, Hansen sees the potential to preserve his family’s farm and a way of life he holds dear, especially as the climate changes.

“You’ve seen what the land looks like in five years; imagine it in 10,” Hansen said. “If we can do it here, we can do it anywhere.”

July 30, 2025

From Oklahoma to D.C., a food activist works to ensure that communities can protect their food systems and their future.

Leave a Comment