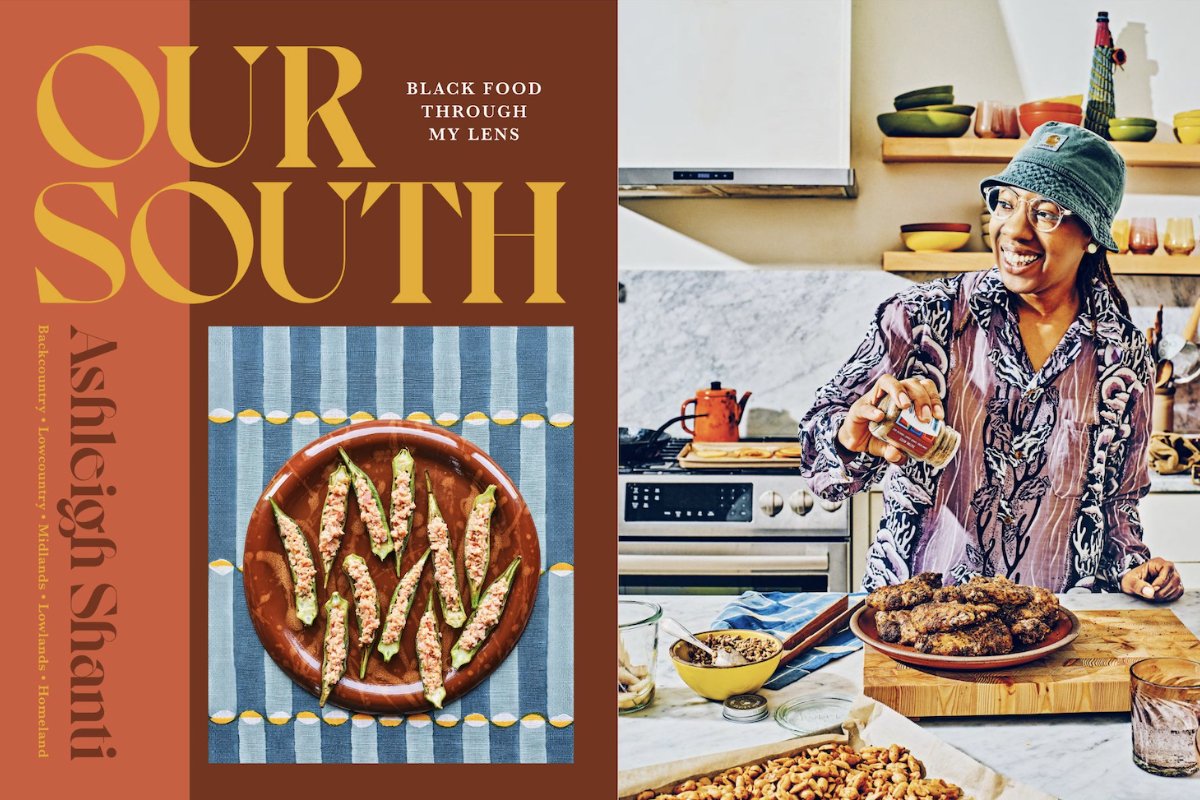

The new cookbook from ‘Top Chef’ alum Ashleigh Shanti features recipes from five micro-regions of the American South.

The new cookbook from ‘Top Chef’ alum Ashleigh Shanti features recipes from five micro-regions of the American South.

December 2, 2024

(Photo credit: Johnny Autry)

A version of this article originally appeared in The Deep Dish, our members-only newsletter. Become a member today and get the next issue directly in your inbox.

Expand your understanding of food systems as a Civil Eats member. Enjoy unlimited access to our groundbreaking reporting, engage with experts, and connect with a community of changemakers.

Already a member?

Login

Ashleigh Shanti says she’s “out to prove something” with her debut cookbook, Our South: Black Food Through My Lens, which hit shelves last month.

“I want to dispel the myths of what America thinks Black cooking is and is not,” she writes in the opening pages. “Through my stories, recipes, and experiences, I challenge the belief that Black cuisine is monochromatic.”

Named one of “16 Black Chefs Changing Food in America” by the New York Times, Shanti has been hard at work building her legacy as a Black, queer woman in the culinary world. In 2020, she earned a James Beard nomination for Rising Star Chef of the Year, recognizing her “Affrilachian” cooking at Benne on Eagle in Asheville, North Carolina. After that, she dazzled American television viewers on season 19 of Bravo’s Top Chef. Earlier this year, she opened a fish-fry restaurant, Good Hot Fish, in Asheville’s historically Black business district, earning accolades from Eater as one of the best new restaurants in America.

Now, the Virginia native blesses us with a cookbook that doubles as a memoir, honoring the Southern matriarchs in her family while celebrating the culinary diversity of the Black diaspora. Featuring 125 recipes and vibrant photography by Johnny Autry, Our South takes readers on a journey through five southern micro-regions—each revealing its own “courses and customs”—and people who shaped Shanti into the chef she is today.

Between stops on her book tour, Shanti took a moment to speak with Civil Eats about Black food, queer voices in cooking, and what it’s like to be a restaurant owner in post-hurricane, post-election Asheville.

When and why did you decide to write this cookbook?

In 2020, a literary agent named Rica Allannic approached me about writing a cookbook. At the time, I was incredibly burdened by my chef position [at Benne on Eagle]. It was a very high-pressure job, with the restaurant open seven days a week for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

Like a lot of people during 2020, I had a moment of reflection where I asked myself what I was doing and what legacy I was leaving. I had never opened my own restaurant, never even done a popup or anything like that. What I needed at that time, or what I wanted most, was to feel like I had a voice.

It was important for me to document these recipes, not just for me personally. I feel like there are so many foodways and traditions within Southern cooking that are kind of dying. A lot of the recipes in my family weren’t even written down. If I wanted to know how to make something, I had to call my auntie, or my mom had to track down little handwritten pieces of paper.

In the introduction, you write that you “want to dispel the myths of what America thinks Black cooking is and is not.” What are some myths of this type you see perpetuated in the culinary world and beyond?

When our industry, our nation, hears of a Black chef, they automatically put us into a box and expect a certain cuisine of us. If someone makes fried chicken, that is suddenly their identity. I love fried chicken, and it’s in the cookbook, but the South has so much more to offer when it comes to our foodways. I have a best friend who is a Black chef in Louisville, and he’s making amazing Asian food. The diaspora is so vast, and there are so many influences we pull from, but people don’t really dig deep into what our foodways look like.

I think about how I grew up eating more vegetables than meat, which was secondary on the plate and there to bring flavor; it wasn’t the star of the dish. When it comes to agriculture and farm-to-table cooking, those things for me are synonymous with the ways we cook in the South. I wanted people to walk away from the cookbook not just with the knowledge of how to make really great recipes; I wanted them to gain a deeper understanding of the South. I do believe that this book offers something that other Southern cookbooks don’t.

How did you come to know the micro-regions highlighted in the book?

I identify with the micro-regions because of familial connections. I grew up in coastal Virginia. I have family on my dad’s side from Charleston, South Carolina, and kind of spread out all over the state. My mom’s side is in western North Carolina and southwestern Virginia. I didn’t set out to write a book that was divided by region, but writing it helped me understand who I am as a chef, why I cook the way that I do, why my mom’s rice is boggy and why my dad likes his rice dry, or why my mom uses a splash of apple cider vinegar and black pepper to season—that is a very Appalachian thing to do. I don’t even think I realized these things until I started documenting these recipes and tracking down all these food memories and seeing there was a common denominator through a lot of them. Certain regions cook a certain way.

“A big part of why I’m in the service industry is because of the feelings a good meal has the power to evoke in people.”

You have a “U-Haul” shrimp cocktail recipe, referring to the stereotype of lesbians who fall in love and move in together “at lightning speed.” As a U-Hauler myself, this gave me a chuckle. Has it always been important for you to celebrate queer identity or culture in your culinary work? And what has that looked like over time?

I’m glad you understood the title of the recipe. I had to explain it to my publishers. Identifying as a Black queer chef is obviously incredibly important to me. It’s who I am. I don’t remember seeing anyone like me coming up in the industry. That’s what drives me to be forthright and loud about my queerness and my Blackness: I want other people who are struggling to find themselves to feel like they’re represented.

Aside from the U-Haul recipe, is there one dish or technique in the book that you think might surprise people?

I am always surprised to hear that people don’t know what leather britches are. Stringing britches [green beans] on my aunt’s porch is such an early food memory of mine and something I thought everyone did. It [connects to] these really fancy, high-end kitchens that dry vegetables and then rehydrate them to intensify and concentrate the flavor. It’s a very technique-driven thing that grandmas have been doing for centuries. Whenever I talk to people about britches, they’re pretty fascinated.

What are some essential ingredients or techniques you feel home cooks should learn, to get the most out of your recipes in this book?

Well, I would direct them to the “Supreme” [chapter] at the beginning of the book. I feel like being able to make potlikker and even understanding the concept of what potlikker is goes a very long way in cooking. You’ve also got to know how to make a pot of rice—that’s very important. Also, they should understand the versatility of something like cornmeal and be able to do a gluten-free dredge or make a nice cornbread. Readers will find what they need to know instantly in opening this book because I detail all of this in the first chapter.

How would you describe your restaurant Good Hot Fish?

I would describe it as a modern-day fish camp. That was the idea in my creation of it—a fast-casual counter service spot. We play jazz music. There are pictures of old Black Asheville all over the walls, and little trinkets and artwork that my wife, Meaghan, created. We’re all decked out in the restaurant with some really cool stuff. We get fresh seafood daily that’s local, and we source from local farmers. We also pay a livable wage of $23 an hour, which is very hard to do in Asheville.

Multiple times people sitting at the counter have told me that our food at Good Hot Fish reminds them of a meal their grandmother would make. That makes me so happy to hear, especially where we’re nestled, in the South Side (now called South Slope) of Asheville, which was formerly a Black business district. There is not a whisper of that anymore, unfortunately. I mean, there is another Black restaurant and a couple of food trucks, but there are no full-service Black-owned restaurants in Asheville anymore. If you look in the Green Book, you can see that there were plenty. I know some elders in the community who had restaurants in that area, and it was so incredible when we first opened to have them come through our doors—with tears in their eyes

I saw on your Instagram account that Asheville’s culinary community is involved in ongoing relief efforts. What are you all doing—and how’s that going?

One thing that we started doing in the midst of our closing is start what’s called Sweet Relief Kitchen, a free fish-fry popup supported by food donations. (Good Hot Fish had to close after Hurricane Helene and reopened on November 15.) We are cooking for free and going to underserved communities, posting up at their local church or park, putting the word out, and feeding as many people as we can. We’ve fed hundreds of people, which feels really good.

How can people best support Asheville’s culinary community?

I’m hoping for an Asheville Renaissance when all this is over. It’s really encouraging to ride down the same street every day and start to see some progress, like trees getting cleared out and mud scraped away. We are doing our best in a city driven by tourism to ensure that tourists can come back and have an amazing time in Asheville. I would encourage people to visit our city and support our small businesses, our restaurants. We’re a city that has so many makers, and we’re working to get everything back to normal as possible in hopes that tourists will support us when this is over.

Since the election, I’ve been thinking about John T. Edge’s book, The Potlikker Papers, about the Black women who fed freedom fighters during the Civil Rights Movement, and the role of food and cooking in our current moment. What does food do for you in times like these?

Cooking is such a meditative practice for me that all I want to do is cook right now. When I’m feeling emotional, the first thing that I want is my mother’s food, something comforting, a bowl of beans or some of her stewed greens. I certainly turn to food when my emotions are heightened, whether that is joy or sadness, and I think a lot of people feel that way. A big part of why I’m in the service industry is because of the feelings a good meal has the power to evoke in people.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

July 30, 2025

From Oklahoma to D.C., a food activist works to ensure that communities can protect their food systems and their future.

Like the story?

Join the conversation.