‘The Wisdom of the Hive’ explores the short, selfless lives of honey bees, defined by mutual caretaking and attunement to the larger ecosystem.

‘The Wisdom of the Hive’ explores the short, selfless lives of honey bees, defined by mutual caretaking and attunement to the larger ecosystem.

July 21, 2025

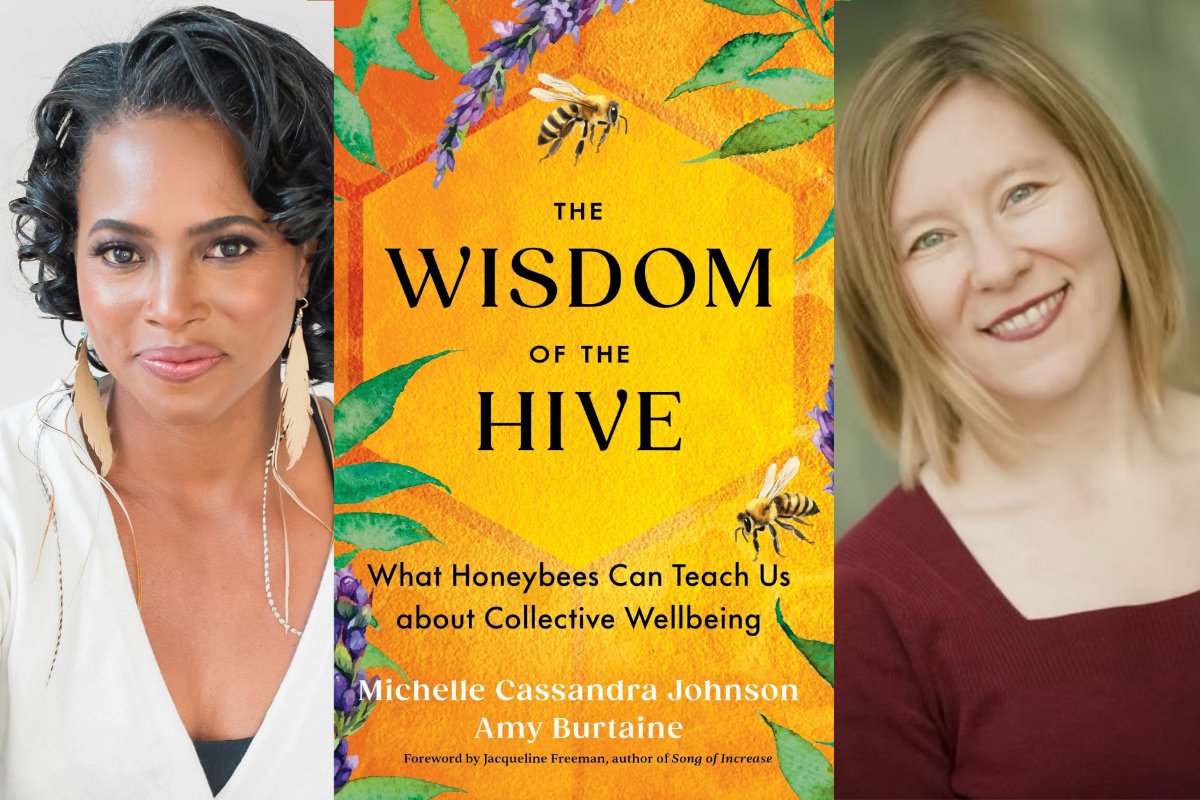

Authors and beekeepers Michelle Cassandra Johnson and Amy Burtaine.

A version of this article originally appeared in The Deep Dish, our members-only newsletter. Become a member today and get the next issue directly in your inbox.

Expand your understanding of food systems as a Civil Eats member. Enjoy unlimited access to our groundbreaking reporting, engage with experts, and connect with a community of changemakers.

Already a member?

Login

About 35 percent of the world’s food crops are dependent on pollinators, which means that we have them to thank for about one in every three bites of food that we eat. Whether or not you welcome the presence of bees at your picnic or party, there’s no denying our tables would be poorly set without them.

Michelle Cassandra Johnson and Amy Burtaine, co-authors of The Wisdom of the Hive, understand this about bees—and much, much more. Johnson began keeping bees at her home in North Carolina in 2019, prompted by a vivid dream about them at a time when her mother was gravely ill. Still half dreaming, she got online and ordered “everything that one needs to tend bees—the suit, the boxes, the bees, everything,” she says.

Soon afterward, she learned that in many cultures, bees are thought to help people through times of grief or uncertainty. “This is when I began to understand their mystical power,” she writes in the book. (Her mother eventually recovered.) “And when the shipment of bees arrived, I began to realize the very practical magic they embody.”

“What does it mean for us as humans to labor in a way that will support future generations, even if we won’t experience that ourselves? To me, that kind of laboring is a condition that needs to be in place for us to create justice.”

Burtaine started keeping bees a year later at her home off the coast of Washington state. Though she still does not feel like a master beekeeper, she’s had great teachers—millions of them. “I am always learning from the bees,” she says.

The two longtime friends, who both work as equity educators, experienced the joys and heartbreaks of beekeeping in their respective backyards—from the sweet taste of a hive’s first honey harvest to the silence of a colony lost to a bitter cold winter day.

Then, one day, Johnson called Burtaine and invited her to a shamanism workshop about the principles of the sacred feminine and bees. Burtaine recalls, “At the end of it, we turned to each other with so much excitement. It felt like everything that bees do is a metaphor for humans, which could be a lesson to us.”

That excitement sparked a creative collaboration that eventually took form as their new book, in which the authors invite us to reflect on the myriad complex relationships between humans, bees, and the planet we all share. They encourage us to reimagine the relationship between humans and bees as one defined not only by what the bees can provide us tangibly in the form of honey, but also by the life lessons they can offer if we really pay attention. And, as bee populations the world over have plummeted, resulting in resounding chants of “Save the bees!” Johnson and Burtaine ask instead: “What if the bees are here to save us?”

Civil Eats recently spoke with the authors about bees and what they can teach us about the attunement, caretaking, and interconnectedness that are vital to their survival—and, the authors believe, to ours.

What are some of the ways that we all live in relationship with bees, even if we don’t tend beehives?

Burtaine: Michelle and I did not write this book only for beekeepers. We wrote it as a love letter to bees and as a love letter to humanity. We see how bees treat one another and care for the hive as a superorganism in ways that we wish human beings modeled. Our mission with the book is to help people become students of bees, like we are. Even if you’re not a bee-tender, you’re a food eater—and there’s food injustice across the planet because of systems of oppression. We have things out of balance as humans because of our hierarchies, with us at the top, even though we couldn’t survive without pollinators.

There are also incredible statistics—something like two million flowers go into a pound of honey. It’s just one example of how bees work. Even if they won’t be able to benefit from or taste the fruits of their labor, bees are constantly laboring for future generations, and for us.

Johnson: I think we have forgotten who we are to each other and how to be in reciprocal relationship with the more-than-human world, which is making us suffer. Most of what we ingest is in some way touched by the honey bees, which should call us into a deeper relationship with them.

It makes me think about the life cycle of most bees, which is about six to eight weeks, with the exception of the queen. Throughout that cycle, they’re moving through different roles within the hive. Their final stage is being a forager, where they go out and gather resources, like pollen and nectar and water, for the hive. Often, they will not benefit from those resources directly, because they’re going to die soon.

So, a question we ask is: What does it mean for us as humans to labor in a way that will support future generations, even if we won’t experience that ourselves? To me, that kind of laboring is a condition that needs to be in place for us to create justice.

What are some of the surprising things you’ve learned about how bees interact with each other? What can they teach us about community?

Johnson: As a superorganism, bees do not think of themselves as individual bees—they think of themselves as an extension of the hive. Everything they do is for the hive. They also work with the ecosystem. They understand seasons and weather systems—they know if it’s going to storm well before we do. They work with the sun and light. They work with the things that are blossoming outside their hive. Bees have to understand all that to survive. What if we understood and were aligned in that way with the larger ecosystem?

Bees are also an indicator species—how well bees are doing is an indication of how well we are doing.

“We’re in a time of great uncertainty, and it’s scary. What if we were to—as the bees do—huddle together in the dark, instead of just figuring out ‘how do I survive?’ or ‘what do I need?’”

Burtaine: Bees attune to one another. Their vibration tells you how they are doing. When they are agitated, their vibration is higher. When they are calm, their vibration is lower. They work well together, whether under stress or not.

We as humans tend to fall apart under stress. We are not resonating with ourselves. We are not resonating with one another or doing what is best to help those right next to us. We are not tuning into the whole. We in the West are from a “save mine, get mine, hoard mine, figure out mine” culture that is antithetical to what the bees do. The bees could never do anything for individual gain.

How do you think bees should inform our response to the present moment, to what’s happening in politics and social systems?

Burtaine: So much of what bees do is in the dark [of their hive], but as human beings, we tend to fear the dark. It’s the land of our nightmares, myths, and legends; it’s full of monsters or the wild beasts that would eat us in the days before electricity.

There’s a beautiful writer, Francis Weller, who does a lot of grief work and talks about the period we’re in being “the long dark.” We’re in a time of great uncertainty, and it’s scary. What if we were to—as the bees do—huddle together in the dark, instead of just figuring out “how do I survive?” or “what do I need?” What if we embraced the unknown? What if we sit more kindly with ourselves and one another in the unknowing to create new visions, new ideas, new possibilities?

I think we’re at a time on the planet where we have to learn by doing. We cannot wait until we’re ready with things figured out. We’re not going to just get it right. We’re going to move messily through it together.

Johnson: One way we can learn to mirror the ways of the bee is to attune to our internal and external landscapes. People right now are dysregulated, distracted, and overwhelmed, so it’s very hard to show up moment after moment.

The bees tend to one another, and they tend to the hive. That laboring and care and attunement feel like skills and tools that people in our ancestral lineages understood, because they were more connected to natural rhythms and engaged in ceremony related to seasonal shifts. They were more closely aligned to agriculture in the sense of “what’s growing now?” not “what do I want to eat right now?”

It’s going to require us to understand that things are urgent, and also that a response to this urgency is us slowing down enough to understand what is happening. The bees model that all the time. They’re aware of everything that is happening within and outside the hive, and they’re communicating about it through their antennae, vibrations, and movements.

How can folks become more attuned to bees and begin to learn for themselves what bees have to teach us?

Johnson: A practical thing people can do is plant a pollinator garden or support a community garden. That practice of gardening with one another generates a sense of hive mind.

Burtaine: Honey tasting is a practice we suggest, as long as folks aren’t allergic. Sit with the incredible complexity that unfolds when you really taste it. There are stories in honey.

Johnson: There are hints of multiple plants and places [in honey]. It can be a beautiful meditative practice to both nourish your body and be really present to the complexity and sweetness of what the bees offer.

What are some things we can all do now to better care for the bees, ourselves, and those around us?

Burtaine: There are very practical things we can do. If you have the means, support local, organic farmers and beekeepers. Don’t use pesticides. Try humming—it’s a powerful nervous-system-settling practice that you can do by yourself. You can also put on a YouTube video to listen to the bees and hum along with them, or try a humming practice or attunement meditation.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

July 30, 2025

From Oklahoma to D.C., a food activist works to ensure that communities can protect their food systems and their future.

Leave a Comment