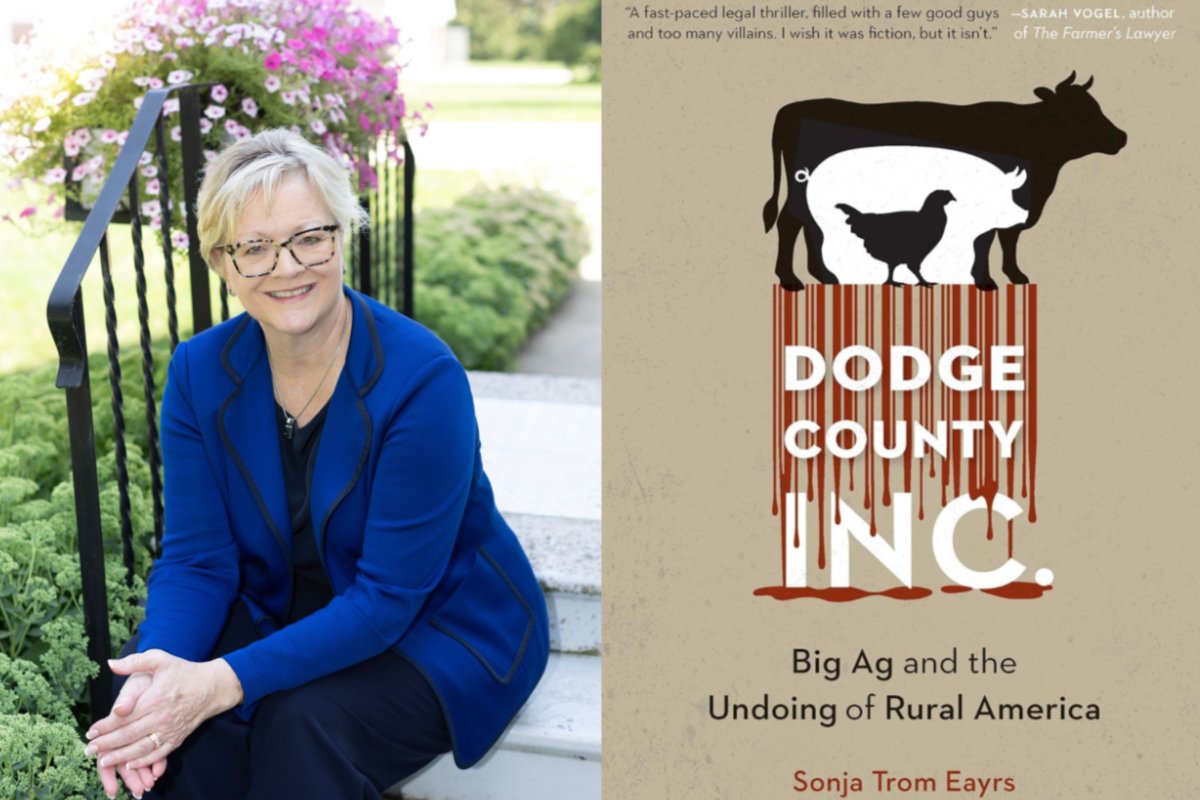

In a new book, Sonja Trom Eayrs chronicles her family’s battle against factory hog farms in Minnesota.

In a new book, Sonja Trom Eayrs chronicles her family’s battle against factory hog farms in Minnesota.

November 18, 2024

In 2014, Lowell and Evelyn Trom learned that a farmer wanted to build a concentrated animal feeding operation (CAFO) across the road from their family farm in Blooming Prairie, Minnesota. By then, there were already 10 CAFOs within a 3-mile radius of their 760-acre farm, so they knew the stench the facility would bring.

Expand your understanding of food systems as a Civil Eats member. Enjoy unlimited access to our groundbreaking reporting, engage with experts, and connect with a community of changemakers.

Already a member?

Login

The proposed CAFO would hold 2,400 pigs and produce as much manure equivalent as a town of nearly 7,000 people. “Enough,” Lowell said, “is enough.” The couple sued, assisted by their daughter, Sonja Trom Eayrs, a Minneapolis family law attorney who felt a deep sense of responsibility to help her elderly parents. Their legal battle took three years, and by the time they lost, nothing had changed—except a county ordinance had been created that made it easier to greenlight even more CAFOs. The CAFO they fought was built and is still operating across the road from their farm today.

The battle inspired Trom Eayrs to become a rural activist and help other communities fight what she calls a CAFO “takeover” of the Midwest. And it prompted her to write a book about her late parents’ experiences: Dodge County, Incorporated: Big Ag and the Undoing of Rural America, published on November 1.

“It tears at the fabric that traditionally tied people together. The days of being a good neighbor and helping one another are gone. The factory farm fights have been so divisive, pitting neighbor against neighbor.”

In the book, Trom Eayrs argues that rural America is transforming into a corporate entity, one CAFO at a time. Since 1990, the number of U.S. hog farms has shrunk by more than 70 percent while individual farms have gotten bigger.

Trom Eayrs writes about the “Big Pig Pyramid,” a three-tiered, vertical integration model in which multinational meatpacking conglomerates sit at the top, followed by “integrators” in the middle tier that own the hogs and provide feed and veterinary services. At the bottom are the contract growers—a mix of fellow farmers or farmers from out of state—who raise the pigs in CAFOs, sometimes with the help of immigrant workers.

Besides causing air and water pollution, CAFOS can harm communities in other ways, Trom Eayres says. If you’re near a CAFO, being outside can be risky: Once, when her dad was harvesting the last of the corn, the CAFO across the road spread its manure on fields surrounding the Trom farm, and she says her dad became so dizzy he had to get off the combine to vomit.

Neighbors end up with an eroded quality of life, trapped inside their houses by the stench and dangerous emissions, she writes. And she describes how battles over CAFOs have led to what she characterizes as intimidation and suspicion, stifling those who would speak out against the feeding operations and creating a chilling effect in towns where mutual respect was once the norm.

Using her hometown and family as the backdrop, Trom Eayrs details the influence of corporate interests and the Farm Bureau at all levels of government. For example, she describes how the agricultural industry backed state Right to Farm laws that limit residents’ ability to file nuisance actions against CAFOs once they’re up and running. The Farm Bureau and allied industrial agriculture interests wield incredible influence in Washington, D.C., regardless of who is in power. Trump is now vowing to eliminate corporate influence within federal food and agriculture agencies, but during his last administration, that influence increased significantly.

Civil Eats recently spoke to Trom Eayrs about her family’s battle against CAFOs, the ways these facilities hurt rural areas, and how communities are fighting back.

Could you describe the social impacts that communities face once these operations arrive?

I don’t think people realize how destructive the CAFO system is to rural communities. It tears at the fabric that traditionally tied people together. The days of being a good neighbor and helping one another are gone. The factory farm fights have been so divisive, pitting neighbor against neighbor. Eventually, we will learn that we need one another.

My family has faced harassment and intimidation for years. I’ve had to file several complaints with the Dodge County sheriff’s office and ask for extra patrols near our farm. Constant garbage [being dumped on our property], harassing telephone calls to my father in the middle of the night. One day, my brother and I were pulling weeds from the bean field, and a couple hours later, the stop sign maybe 100 to 200 feet away was sprayed with bullets.

I’m in a unique position because I don’t live in my home community. I don’t go to church there, and my children never went to school there, so I don’t have to see these people on a daily or weekly basis. But people [who live] in these small rural communities feel this tension.

For me, [the harassment] is confirmation to keep going. Don’t let them intimidate you. Keep digging for information. I know their playbook.

How would you describe the CAFO industry playbook?

It follows the classic teachings of Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, which is included in the curriculum in many business schools.

The corporate state has had its eyes on rural areas for years, adopting Right to Farm laws—which I frequently refer to as “Right to Harm” laws—placing the [agricultural] industry in a power position over farm families who have lived on the land for generations.

In repeated CAFO fights, the industry employs the classic sneak attack, laying plans weeks, months, and years ahead of construction. The multi-step process of siting, permitting, and construction occurs in secret, and neighbors are alerted at the last possible moment.

The industry sugarcoats the true impact of CAFOs on the environment, neighbors, and community. They dismiss the seriousness of the dangerous air emissions and often refer to it as the smell of money. Then why was my father vomiting?

This CAFO, located across the road from the Trom family farm, sparked multiple lawsuits. (Photo credit: Laurie Schneider)

It has created propaganda and indoctrination materials, including children’s coloring books. For example, I picked up a coloring book at the Minnesota State Fair that was produced by the National Pork Board and the Minnesota Pork Board. It’s another effort by the industry to polish its image.

Industry insiders repeatedly use harassment and intimidation tactics to silence opposition, including menacing phone calls threatening local businesses that oppose their plans. I also know of residents whose livelihoods were threatened when they showed support for laws that would limit the construction of CAFOs.

Although you wrote that “defeat was all but certain,” your family still decided to fight the CAFO across the road. Why?

My dad was a warrior. He would always say, “All we did was fight that goddamn Farm Bureau.” He was repeatedly asked to join the Farm Bureau, but he always declined. Other people wouldn’t take up the fight. They just allowed the big boys to roll right over them. My dad was sharp as a tack: He understood the seriousness of what was going on, and he could see the big picture.

Toward the end of his life, it started to take a toll on him, and I recall him saying, “I’m tired of being the goat.” In other words, he was tired of being the object of ridicule in the local community. I purposely went to church with my dad. I could see that he was essentially persona non grata in my home community. People wouldn’t speak to him.

These large industrial operations [still] impact my family and the daily use and enjoyment of our farm. The choking stench coats your nose and throat, and you have to immediately retreat indoors. I have a large family, and our farm has served as the central gathering destination for many gatherings over the years. [Now, there are] no more family reunions. No more picnics. No more weddings and wedding receptions.

What are the most effective tools rural residents can use to fight CAFOs in their communities?

Number one, education. People need to understand the big picture, that rural America is slowly, methodically, being corporatized, and that the industry is very good at operating under the radar. The corporations derive their strength in two ways. They’ve got market control, and they use their political ties and connections to force their corporate agenda onto the American public. They have a combination of market power and political power, and they will do anything to stay in power.

Number two, organization. Go door to door, talk to your neighbors. Reach out to state or national organizations for assistance. At the end of the day, it’s really a fight between community and corporations, which is why I call the book Dodge County, Incorporated: I want to drive home the fact that corporate governance has found its way into local governance. That’s happening at every level—at the township level, the county level, the state level, and the national level.

Dodge County citizens, joined by the Land Stewardship Project, are shown protesting the proposed Ripley Dairy on the county road bordering the Trom family farm. (Photo courtesy of the Land Stewardship Project)

In my book, I talk about the [successful] battle against the Ripley Dairy, which was going to be three or four miles north of our farm over 20 years ago. That fight, a citizen’s effort that included members of my family, went on for three or four years. That was successful because the neighbors worked cooperatively and with the assistance of the Land Stewardship Project, which had experience in these fights. They were a critical partner. It was an effective and organized protest.

There’s a group in western Wisconsin that has done phenomenal work. They had a bipartisan group in six towns and were able to adopt planning and zoning at the local level to limit the proliferation of CAFOs.

You write in the book that “this journey of heartache and sadness has turned to hope and determination to fight for Big Ag reform.” What did you mean by that?

When factory farm sites come up [in their towns], people feel very isolated. They don’t know where to turn for help. They don’t understand the enormity of the issue.

But for me, in the last 10 years, I started making connections with folks all over the Midwest and a number of different organizations like Farm Action and Food & Water Watch and realized that we were not alone. That’s empowering.

What do you hope your book will achieve?

People in these rural communities have a trail of abandoned schools and abandoned churches, and they are going to realize that they’ve been played, they’ve been rolled over by the big multinationals. I think [this book] is going to be eye-opening for some of these folks.

I’m hoping that the book will provide some historical context and a deeper level of understanding, and then help people understand what they can do in their own communities to move forward.

Not everyone lives near a CAFO. What can they do to help fight the “CAFO takeover”?

People need to be mindful of what they’re eating. What’s the source? Did this come from a corporate factory farm, or is it from a local, independent farmer who lovingly raised this animal?

Also, it’s not enough for people to sign a petition to fight a CAFO. We need to educate politicians. We need to roll back these Right to Farm laws that are designed to benefit corporations. And that’s going to take [effort from] everyone.

This interview, conducted via phone and email, was edited for length and clarity. This article has been updated to clarify CAFO ownership and workforce structures.

July 30, 2025

From Oklahoma to D.C., a food activist works to ensure that communities can protect their food systems and their future.

Like the story?

Join the conversation.