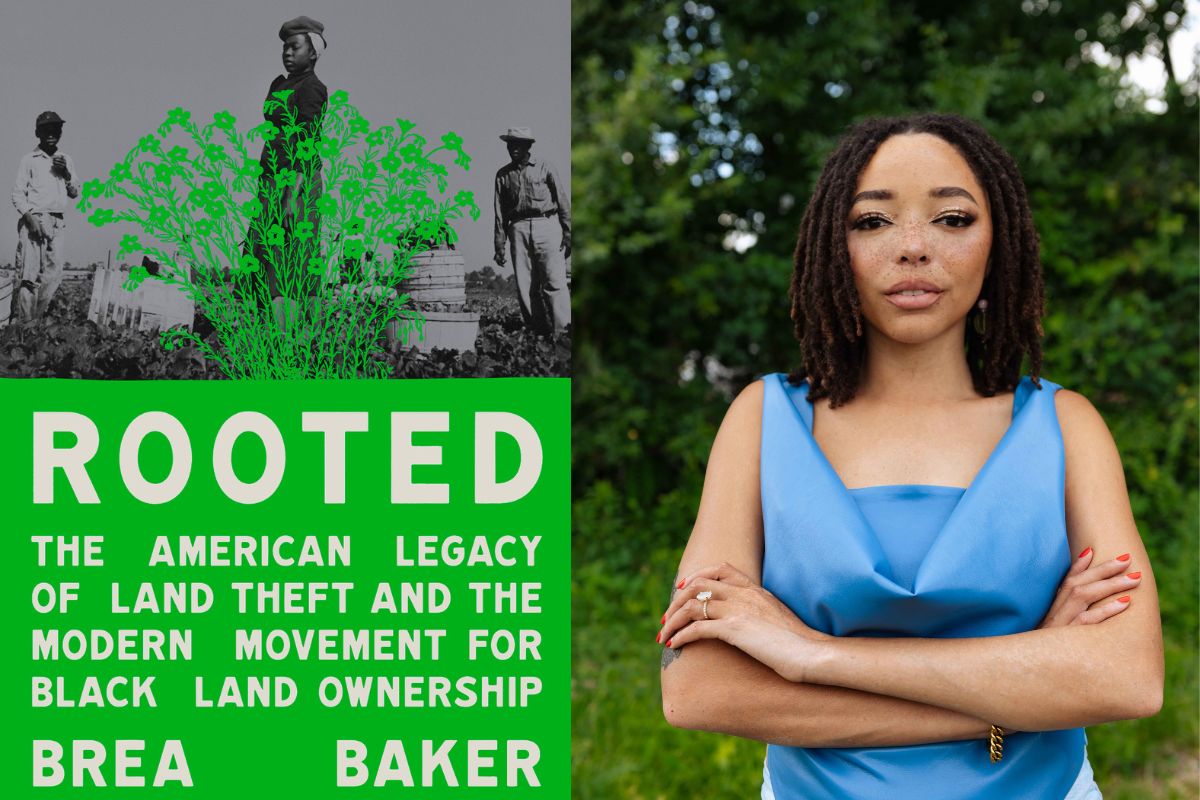

The author of ‘Rooted: The American Legacy of Land Theft and the Modern Movement for Black Land Ownership,’ talks about her family’s farming history, the lasting impact of land loss for Black people, and the case for reparations.

The author of ‘Rooted: The American Legacy of Land Theft and the Modern Movement for Black Land Ownership,’ talks about her family’s farming history, the lasting impact of land loss for Black people, and the case for reparations.

February 3, 2025

(Photo credits, left to right: Bridgeman Images for One World/Random House and Inari Briana).

Brea Baker remembers spending a lot of time in her grandparents’ New Jersey home with piles of paper everywhere. Her grandfather, Alfred Baker, worked to ensure the family was never tricked out of anything rightfully theirs, considering the precarity of Black land ownership in the American South. Her grandfather stressed the importance of keeping a paper trail, such as receipts for property taxes and deed records to prove ownership.

Expand your understanding of food systems as a Civil Eats member. Enjoy unlimited access to our groundbreaking reporting, engage with experts, and connect with a community of changemakers.

Already a member?

Login

Baker was an undergrad at Yale in 2015 when the Black Lives Matter movement—just two years into its existence—started to grow. She began to ask herself, and her grandfather, more questions about her family’s story and their relationship to land, and saw how that history connected to her student activism.

Then, in 2019, her grandfather passed away. She was left with half-opened conversations, but they created enough of a blueprint for her to begin piecing together the Baker family’s multigenerational farming legacy through historical research. Her findings led her to write her debut book, Rooted: The American Legacy of Land Theft and the Modern Movement for Black Land Ownership, in which she lays out the violent expulsion of Black farmers and landowners across the American South.

“We need to get to a place where most Americans finally believe that we need to address the legacy of slavery and start talking about what that would look like.”

Baker’s book is a memoir, a history, and an argument for Black Americans to return to rural life. It reveals the deliberate ways in which agricultural policies and Jim Crow violence harmed the Black land economy, including that of her family. Baker also describes the many land-return and reparations advocacy movements reshaping the conversation around Black and Indigenous land stewardship.

The book opens with a brief history of U.S. governmental policies, starting in the late 1700s, that stripped Indigenous communities of land and wealth. Baker then covers the sharecropping economy and the Great Migration, spanning the mid-1800s through the early 20th century, when Black people transitioned from enslavement to a level of autonomy. Rooted takes us into the present day by laying out the case for reparations as a foundational policy for racial, economic, and environmental justice in the United States.

Today, Baker is a writer, speaker, and anti-racism consultant. When she’s not writing and traveling, she raises chickens and fruits and vegetables like spinach, rhubarb, and tomatoes on an acre of land she shares with her wife and son in Atlanta. We spoke to her recently about the deeply personal and important historical events she’s covered in her book, and her thoughts on where the land justice movement goes from here.

Tell me about your family’s farming legacy and story of land ownership.

I am a sixth-generation Black landowner. The first [Black] person in my family to own land was my great-great-great grandfather, Louis W. Baker, on the paternal side of my family—so we have this longstanding legacy of farming and land ownership.

Louis W Baker had two sons who helped him maintain the farmland in Warren County, North Carolina in the mid-1860s. Generations later, starting around the 1950s, my great-grandfather, Frank L. Baker, lost a lot of land, mostly due to a significant dispossession period during the 20th century for Black farmers and landowners. This was due to predatory property tax increases and debt. As a result, much of that land ended up in the hands of corporations and the state.

My grandfather, Alfred Baker, and many of his siblings ended up traveling north by way of the Great Migration, and that ultimately whittled away at the ability to maintain the farm as a family-owned business.

We do still have something, and that is a beautiful thing. My grandfather spent his entire pension buying more land that he would eventually retire on with my grandmother, Jenail Dunlap, and we [the Baker family] started to bring back the farming. My aunt now lives on that land, growing peppers and leafy greens, and she makes these incredible juices and hot sauce—all from what she grows.

What was the spark that ignited you to turn your activism and family research into a book?

I was learning about my family and feeling so much around Tulsa and [the Wilmington Massacre] and so many other stories. So much of your ability to remain connected to agriculture, and know where your food comes from, depends on growing your own food and on having access to land. [Black people have] been robbed, and no one was talking about it.

“We have so many elders around us; before they become ancestors, talk to them. Ask them about their first experiences on land.”

We continue to dance around it, and there’s been no real commitment to anything connected to reparations, even though many of us have a full record of being defrauded.

I felt like my grandfather died trying to make something happen for our family, and he did. We have this beautiful home and acreage, but there’s this story he wanted to tell, which ended up being the basis for Rooted.

In your first chapter, you explore the importance of marronage—the act of freeing oneself from slavery and building an independent community. How does marronage manifest in communities today?

Maroon communities created what they wanted to see for themselves. Today, marronage shows up in how we make ourselves independent of the federal government while still holding the government accountable.

There are no real ways to be a non-taxpayer, devoid of federal government. Many of us are still practicing marronage while being citizens of this country and demanding what our citizenship is supposed to include.

The Black Panther Party was an example of a very maroon-like entity providing the things the community lacked. They filled in critical voids, and that was a very powerful thing to do.

We can find marronage in something as simple as community gardens: We’re going to feed and depend on one another, right?

For example, my wife and I get way more eggs than we can use from our chickens. First, we give them to the family and to our neighbors, and then what’s left, we sell at a heavily discounted price to friends and co-workers.

Our neighbors know they can come to us if needed, and they’re looking out for us in return. This is how we grow interdependence, which is what maroon communities have been about.

In this book, you write that during the Reconstruction Era, land-owning Black people had to learn how to not just own the land but also how to commodify it quickly. How did that shift their relationship to land?

There was this immediate need to learn. Commodification is a form of capitalizing off of something, so we start to see the emergence of Black capitalism, of becoming part of this economy to survive.

When we went off of Indigenous wisdom, societies were much more communalist. Agriculture was very valued, but that was simply one’s job in the community, similar to being an educator, a healer, or a doula. [Our] ancestors had to go from that communalism to being the lowest rung of society as a slave, to then finding a way to make a living off [agriculture]. We had to learn how to put a price on one crop versus another, a price that would make sense to white people.

Trying to figure out a space to be a citizen, a business owner, and part of this agri-economy as a Black person was a delicate dance. But our expertise was often overlooked. I know this soil, I know these trees, I know the stars, I know what that wind means. I know when there’s too much water in the air and when there’s too little water in the air. There was so much innate wisdom, but now they [our ancestors] had to learn the psychology [and business] of making a profit while working with unsavory actors.

It required double consciousness, a concept that W.E.B. DuBois spoke to often.

Reparations for Black land theft is a subject you explore in the book, along with Indigenous land rematriation. How do those conversations make space for one another?

First, it starts with Black and Indigenous people being in community with one another more. We also need to look honestly at Black history and Indigenous history in this country and acknowledge that both cultures have always had an abundance mindset regarding land, that there was enough to go around, that it could be held communally and benefit all of us.

“This country was built on Indigenous genocide, on stolen land, on land that our ancestors worked. All of that deserves repair.”

It is a white supremacist idea that only some of us can have land, and the other people should work it. It is a capitalist idea that the people who own the land would not be those who work it.

The pathways to landback and Black reparations can look very different. For example, in Indigenous communities, landback looks like reclaiming larger swaths of land that are still more rural—and that’s much of what is currently happening in the Pacific Northwest. For Black people, reparations can look like government accountability. States like California are leading the way with initiatives such as forming a reparations task force to address the state’s former participation in the slave economy.

We need to get into the nitty-gritty and be open to the tension. Reparations and landback should be multi-pronged approaches, where people can access resources and assets in the form that works for them. Even more importantly, there is a need for both groups to be in solidarity. I do believe we owe each other something—honesty.

How do we work together and make the case for justice simultaneously so that we are not pitted against each other? We could say, Yes, it’s all stolen land that our ancestors worked on. This country was built on Indigenous genocide, on stolen land, on land that our ancestors worked. All of that deserves repair.

The Pigford vs. Glickman case, which resulted in $1.15 billion in settlements for Black farmers in 1999 and 2010, is considered a hallmark case in addressing alleged discrimination by the USDA. What have been the lasting ripple effects of the settlement—good and bad?

I’ll start with the bad to end on a high note. The negative outcome of the case is that many white people believe that those settlements were reparations. Any new addressing of the issue feels like reverse racism.

We ran into that issue in 2021 when the Biden administration attempted to pass debt-relief legislation for marginalized farmers, which includes white women, women of color, and non-Black people of color. It was portrayed in the media to be only for Black farmers. White farmers saw it as a threat that Black farmers were going to be compensated again and reacted by suing for reverse racism, which kept that money tied up in the courts.

For the Pigford settlements, the message that traveled farthest was that Black farmers were getting money. But many Black farmers did not qualify anymore because they no longer owned their land. To qualify, you had to have existing acreage. If you were already bankrupted and had no money, you could not qualify either. And if you didn’t keep specific records of the debt from the decades that case specified, you did not qualify.

One of the good things about the settlements that did go through is that they kept many farms alive. It was the first time that the government acknowledged that they did not do right by Black farmers and attempted to address it. It was also the first time that the government held the USDA accountable.

I believe that about 20,000 Black farmers and families benefited from the settlements. While that is a large number, we still have less than 1 percent of rural land currently owned by Black people. The problem of the widening racial wealth gap and the lack of Black farming families in the South is still not solved.

What do you hope people take away from your book?

I hope that Black people feel seen and excited to talk to their elders, whether those people are biologically related to them or not. We have so many elders around us; before they become ancestors, talk to them. Ask them about their first experiences on land.

We need to hear those stories, understand the fear, and understand why people do what they do so that we know what we’re fighting against and for. We need to get to a place where most Americans finally believe that we need to address the legacy of slavery and start talking about what that would look like.

I would want everyone to leave the book filled with urgency to act. That starts with learning about your family history through projects like Where’s My Land, which helps Black families reclaim stolen land.

It also looks like working to preserve cultural traditions through food, worker-owned land projects, and resource sharing. It also starts with understanding the fact that we’re never going to get to a post-racial America without some form of reparations.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

July 30, 2025

From Oklahoma to D.C., a food activist works to ensure that communities can protect their food systems and their future.

Like the story?

Join the conversation.