In ‘Group Living and Other Recipes,’ Lola Milholland explores how sharing meals and living space deepens our ability to connect to one another.

In ‘Group Living and Other Recipes,’ Lola Milholland explores how sharing meals and living space deepens our ability to connect to one another.

November 26, 2024

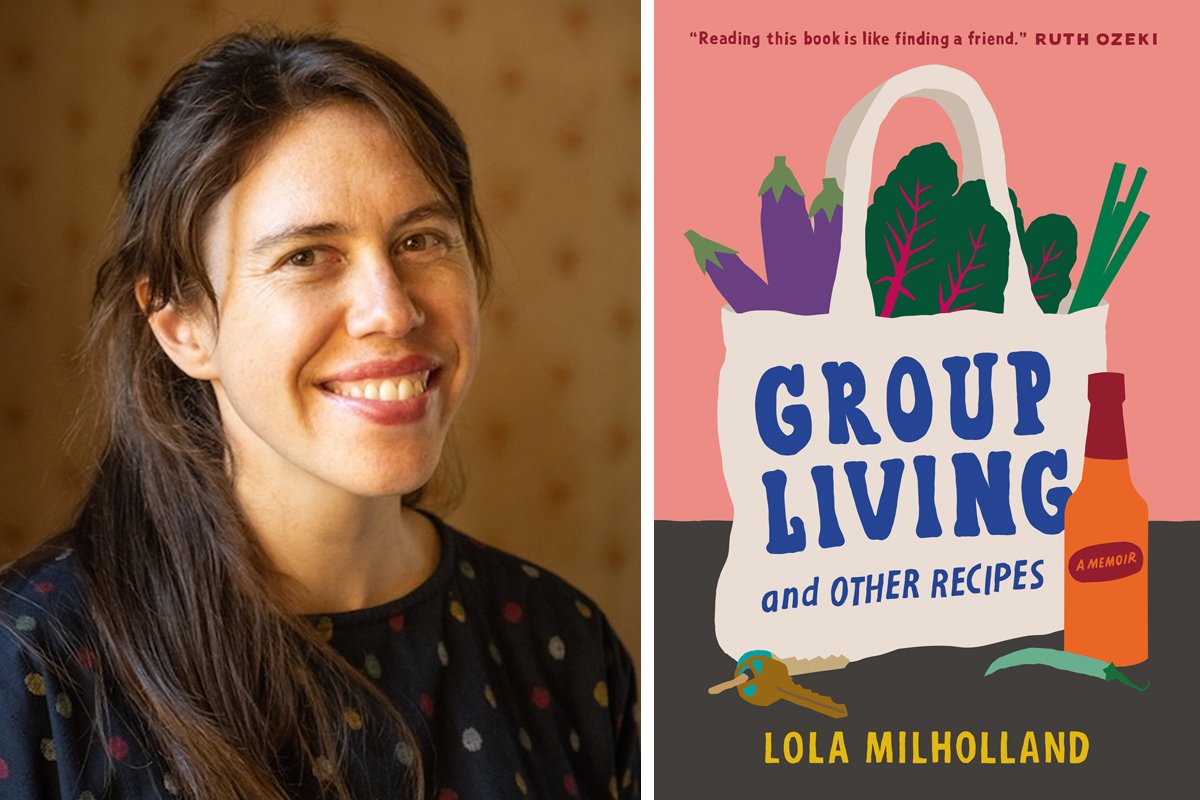

(Photo credit: Shawn Linehan/Spiegel & Grau)

In the first chapter of her book Group Living and Other Recipes, author Lola Milholland writes about coming home from elementary school to discover that her parents had given her bedroom to three Tibetan monks from India. They stayed for three months, and left behind a “sensory collage”—especially the scent of butter as they melted it into their tea, sizzled it with handmade wheat noodles, and shaped it into tiny ceremonial butter sculptures.

Expand your understanding of food systems as a Civil Eats member. Enjoy unlimited access to our groundbreaking reporting, engage with experts, and connect with a community of changemakers.

Already a member?

Login

Then the monks were gone, replaced by a rotating cast of houseguests—relatives, family friends, more than 20 exchange students, and even a group of Indigenous Tairona from Colombia peddling free-trade coffee. Her parents, who lived mostly as roommates, welcomed them all, making “a life together—over days, weeks, months, years.” More guests stopped by for dinner. “There was always room at our table,” she writes.

Milholland, now the founder of Umi Organic, a groundbreaking noodle company in Portland, Oregon, and her brother, Zak, still live together and maintain similar communal living habits at their childhood home, a four-bedroom Craftsman on Holman Street in Portland. As their own unintentional community came together, including a few roommates and regular extended visits from friends and their mom, Milholland became compelled to write a book about her family’s unconventional approach to housing and their long and varied history of cohabitation.

The result is a warm intellectual journey through meals and relationships that invites readers to reconsider the norm of the romantically coupled household. The “recipe” for how to build a household or family can be a loose one, Milholland argues, emerging from lived experiences—just like the recipes that end each chapter, from familiar granola to cantaloupe-seed horchata.

“We got the opportunity to make noodles for schools in 2019, and that shifted my entire understanding of what the business was and could be.”

Milholland worked at the nonprofit Ecotrust for eight years on regional food and farming issues and was assistant editor of Edible Portland magazine before she started her noodle company in 2016. Umi ramen noodles, made from regionally grown and milled flour, were the first certified organic fresh ramen sold in American grocery stores and received a prestigious Good Food Award in 2021.

As we prepare to gather together during the holidays, Civil Eats spoke to Milholland about the lessons communal living can offer us all, the future of Umi Organic, and how stronger relationships and communities can benefit the broader food system, too.

Can you give a sense of the casual intimacies that develop in a communal living situation?

I’ve been thinking a lot about what really breeds intimacy. I don’t think it’s making a date with your friend once a month and having a beer with them for an hour. I think it’s spending time with people in space together. Experiencing each other. What’s the easiest way to be with each other and have that kind of easy contact? It’s having meals together.

Everyone is going to eat dinner. When you eat, you feel really alive. You’re taking care of yourself. You’re taking care of somebody else. You’re offering something of yourself. It may just feel like food, but it’s always more than that. It has to do with the culture that you come from, the places that you’ve been, your relationship to ingredients and the land. What makes you feel good? What kind of effect do you want to have in that moment? And you’re constantly all participating in that, and you’ve just learned so much about each other.

What are meals like at your house?

Most nights we cook and eat together, and special nights can stretch to as many as 10 people.

How do you divide cooking and after-dinner washing up?

I don’t have a problem asking people to help. I usually will just say, “Hey, will you help us peel garlic or wash lettuce?” When people do have a job, I think they get to feel more at home. And the opportunity to show someone how to do something they didn’t know how to do can be quite sweet.

Everybody cleans. Somebody’s unloading the dishwasher and putting the dishes away. Somebody is doing all the dishes. Somebody’s clearing and wiping down all the counters. Someone is putting any leftovers away and asking, “Who needs lunch tomorrow? Pack yourself a lunch.” Usually there’s three or four of us, so it’s quick, you get it done so fast.

How are food expenses shared?

“When people do have a job, I think they get to feel more at home. And the opportunity to show someone how to do something they didn’t know how to do can be quite sweet.”

We split bulk olive oil, bulk organic sunflower oil, bulk rice, and a CSA share. If we buy anything in a large volume, [we’ll split it]. I’m not a great gardener and I’ll buy a huge amount of tomatoes every year and we’ll can them and split the cost. In the past, we’ve even bought a quarter of a pig. Everything else we just buy for ourselves.

We pay for the meals we make, and if you have less money, you might make rice and lentils. And if you have more money, you might make a roast chicken. None of us are expecting anybody to spend some [particular] amount. So, there is an intrinsic sliding scale to it.

What are the dynamics of sharing household chores on a day-to-day basis?

We’re a household without a chore wheel. I think working without one is more egalitarian. We each take turns doing every role. I don’t mind doing certain things, and I really dislike doing others—that’s true for everyone in our household. I don’t mind cleaning the toilet or refrigerator. I’m not great at caring for house plants. It doesn’t mean it wouldn’t be cool for me to learn, but someone else is going to enjoy it, and it’s going to feel less like a job and more like a form of nurturing or care that they give to the house.

It’s not easy to ask someone to do something. You have to do it from a place of sincere desire, knowing that they can ask the same of you, whatever that is, and realizing the stakes feel kind of high.

Let’s come back to the cooking. A lot of the recipes in the book are Asian influenced. What other foods do you make?

Christopher’s [a roommate] influence has made Thai food sort of the beating heart of the household. I always make sure that we have things for a very simple Japanese meal and that makes me feel really grounded.

My brother loves to cook Mexican food. My mom used to make tortillas from scratch when I was growing up. We still have her big, beautiful wooden tortilla press that she carried back from Mexico on buses and hitchhiking in the ‘70s. She used to always make us fresh tortillas and cheese, and my brother’s become a really adept Mexican cook. My partner, Corey, loves Italian food. I love to cook Indian food because it feels so big and flavorful, and you really can eat just pulses [from the legume family] and vegetables.

How did your time in Japan shape your ideas about food?

I went to a public school with a Japanese immersion program, and I visited [Japan] many times before I lived there for a year in college. During that time, I lived with a family who was devoted to regional food. The mother was a professor of food studies and specialized in heirloom pickles. I gained such a sense of what a balanced meal was there. It was really influential.

How does Umi relate to these food experiences?

I don’t think Umi would ever exist if I hadn’t spent that year in Japan, not just because of my exposure to delicious noodles, but also my interest in regionalism. Ramen is really awesome because you go from one place to another in Japan, and each ramen is an expression of place, history, and personality.

I always felt like Umi is supposed to be an expression of place, in this case, the Pacific Northwest. So, we need to be using regional grains. We need to do something that feels connected with the farming community here. I never imagined this brand being national.

Umi’s yakisoba noodles have been served in more than two dozen school districts. How and why did you bring them to the local school food system?

Eventually, we got the opportunity to make noodles for schools in 2019, and that shifted my entire understanding of what the business was and could be. I had this commitment to the producers, to organic, to regionality, and it kept resulting in a product that was expensive. It had this really limited audience, and that didn’t feel right.

When we had an opportunity to make noodles for schools, it felt so much more meaningful and inspiring on a business level. It felt like an opportunity to enact the kind of food system that we want, to continue to hold our values and make it available more broadly. The only thing that made that possible is Oregon’s subsidies for local products for school meals. It’s a beautiful thing; we should make investments that benefit groups, including kids, farmers, food producers, families, local economies. Those things reverberate. It gave me a whole different lease on what the business was and could be.

A fire shut down your operation in June. Are you back in business?

The facility is still not operable, and in the meantime, we found another facility. We’re starting—me and another employee part-time—by just making noodles for schools and then step-by-step decide what we want to grow back into. We have to see if it works financially for us to continue to do this.

I’m calling it a year of experiments. I’m trying to see how I can serve food service, customers, restaurants, schools, corporate cafeterias, colleges. Of course national school lunch will be deeply impacted by the new administration [eventually], but this is a state program! The funding will not be impacted.

You’re in a house that questions tradition, but with the holidays coming, are there any food traditions you’ll be observing?

My mama’s mom always made doughnuts on Christmas morning. I’m not sure if that’s Polish. It’s probably some Polish with Americana combined. It is absolutely crucial to me that fresh, hot doughnuts be made, and these days, with sourdough. With [my grandma], it would have been yeast-raised.

On Christmas Day every year, I always make my grandmother’s doughnuts and invite family, friends, and Christmas stragglers over. We eat doughnuts and drink strong coffee while two of my friends prep their family’s tradition: a full falafel meal.

Because I’ve already got doughnut-frying oil going, it’s no big thing for [my friends] to step in and begin frying falafel. At some point we all sit down—whoever we may be —around our big dining room table covered in pita, hummus, tahini sauce, tzatziki, lettuce, and more, and eat together.

I love, love, love traditions—even if you’re interrogating [some of] them.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Makes 8-10 doughnuts plus doughnut holes

Lola Milholland uses her own sourdough starter for her family’s Christmas doughnuts, which allows for a long, flavor-developing rise. Lola’s grandma made a yeasted version. Depending on whether you choose sourdough or yeast, the timing will be a bit different for the first two steps. In either case, start the recipe early the day before serving.

This recipe can easily be doubled if you have lots of hungry people around your holiday breakfast table.

Ingredients

Sourdough sponge

Yeasted sponge

For the doughnuts

The day before serving, make the sponge:

For the sourdough version, combine the sponge ingredients in a large bowl in the morning and let rest at room temperature in a draft-free spot, covered, for 5-6 hours.

For the yeasted version, combine sponge ingredients in a large bowl in the afternoon and let rest at room temperature in a draft-free spot, covered, for 3 hours.

For both types, make the dough the evening before serving. Add 2½ cups all-purpose flour to the sponge and stir or lightly knead in the bowl until smooth.

The dough should be shiny and bouncy and not too tacky. If it seems like you should add more flour, let the dough rest first, then come back, knead some more, and observe; often it achieves a shiny and bouncy consistency just from having taken a break.

Form dough into a ball, set in an oiled bowl covered with a cloth or plastic wrap, and let rest overnight in the refrigerator.

The next day, turn the dough out onto a well-floured surface. Let rest about 15 minutes.

Roll out or pat the dough until it’s about ½ inch thick.

With a floured doughnut cutter or one large and one small biscuit cutter, cut out doughnuts and holes. Shake off excess flour. Place them on a baking sheet, covered with parchment. Let rest for an hour. They should puff up!

When ready to fry the donuts, heat 2 inches of the oil in a small cast iron pan to 350° F over medium-high heat. Oil is ready when simmering bubbles form around a wooden chopstick or wooden spoon handle inserted into the pan.

Fry one or two donuts and holes at a time, making sure not to crowd them. Turn them only once. Cook for 1 minute per side. Remove and drain on a paper bag.

Fill a small paper bag with ½ cup granulated sugar and a big pinch of fine salt. Add a hot donut to the bag, close it, and shake. Remove the coated donut and repeat with the rest. Serve hot.

July 30, 2025

From Oklahoma to D.C., a food activist works to ensure that communities can protect their food systems and their future.

Like the story?

Join the conversation.