The dismantling of the once expansive agency will not only affect fisheries but also the oceans and weather forecasting. Across the U.S., fishers are already feeling the impact.

The dismantling of the once expansive agency will not only affect fisheries but also the oceans and weather forecasting. Across the U.S., fishers are already feeling the impact.

May 15, 2025

Point Judith’s Port of Galilee, which is vulnerable to rising sea levels and storm surges from ever stronger hurricanes. (Photo credit: Meg Wilcox)

On a cold, bright April day, Sarah Schumann and Dean Pesante are painting the bottom of their fishing boat, the 38-foot Oceana, to prevent barnacles and weeds from attaching. They’re almost ready for the spring fishing season at Point Judith, Rhode Island, New England’s second most valuable fishing port.

Expand your understanding of food systems as a Civil Eats member. Enjoy unlimited access to our groundbreaking reporting, engage with experts, and connect with a community of changemakers.

Already a member?

Login

Schumann and Pesante harvest bluefish, dogfish, scup, and bonito using gillnets that they set daily at the mouth of the Narragansett Bay in Rhode Island Sound.

“Our income and catch have dropped about 30 percent over the last four years,” Pesante told Civil Eats. They’ve caught fewer bluefish in the summer season and found far fewer bluefish during the fall run out of the bay. “We didn’t even reach the quota with what we were landing,” he said.

There are multiple factors that likely contribute to the declining bluefish catch, including rapidly warming ocean waters, which affect fish migration and behavior; dredging to lay cables for offshore wind turbines, which disrupts fish habitat; and a reduced quota for fishers, which explains some but not all of the lowered catch.

“We are looking at an effort to dismantle NOAA as it has functioned for the past few decades.”

For small commercial fishers like Pesante and Schumann, it’s become harder to make a living, and it could get a lot worse. Deep cuts to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the sprawling federal agency charged with monitoring and conserving fish stocks, managing coastal waters, and predicting changes in climate, weather, and the oceans—which commercial fishers rely on for day-to-day as well as seasonal forecasts—threaten the long-term viability of America’s $183 billion commercial fishing industry and the 1.6 million jobs it supports.

Schumann, who founded the Fishery Friendly Climate Action Campaign to give fishermen a voice in advocating climate solutions that work for them, spoke at a House Natural Resource Committee hearing in April about the NOAA cuts.

Though initially buoyed by the Trump administration’s pause on new leases for offshore wind, and its call for a more thorough review process that would heed community concerns, Schumann said she quickly became dismayed by the administration’s wrecking-ball approach to NOAA.

“These cuts will bog down the agency’s ability to serve the public and fishermen at a time when we desperately need—because of climate change—faster, more nimble, and more collaborative data collection and decision making,” she said.

NOAA was formalized under President Richard Nixon in 1970, at a time when rampant overfishing, including by foreign fleets, caused fish stocks to plummet and created hardship for fishing communities. Six years later, Congress passed the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act, setting the rules that govern how NOAA manages fisheries.

In a memo leaked in early April, the Trump administration laid out its plan for slashing NOAA’s overall budget by 27 percent and making other draconian changes to the sprawling agency, including cutting 20 percent of its 12,000-employee workforce.

NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) staff, who oversee commercial fishing and some recreational fisheries, is set to be slashed by nearly 30 percent. The NMFS assesses and predicts the status of fish stocks, sets catch limits or quotas, and ensures compliance with fisheries regulations, working collaboratively with state environmental agencies, the fishing industry, and other federal agencies. It is vital for ensuring the sustainability of U.S. fisheries.

“We are looking at an effort to dismantle NOAA as it has functioned for the past few decades,” said Derek Brockbank, executive director at the Coastal States Organization, a nonprofit that coordinates the work of state coastal zone management offices.

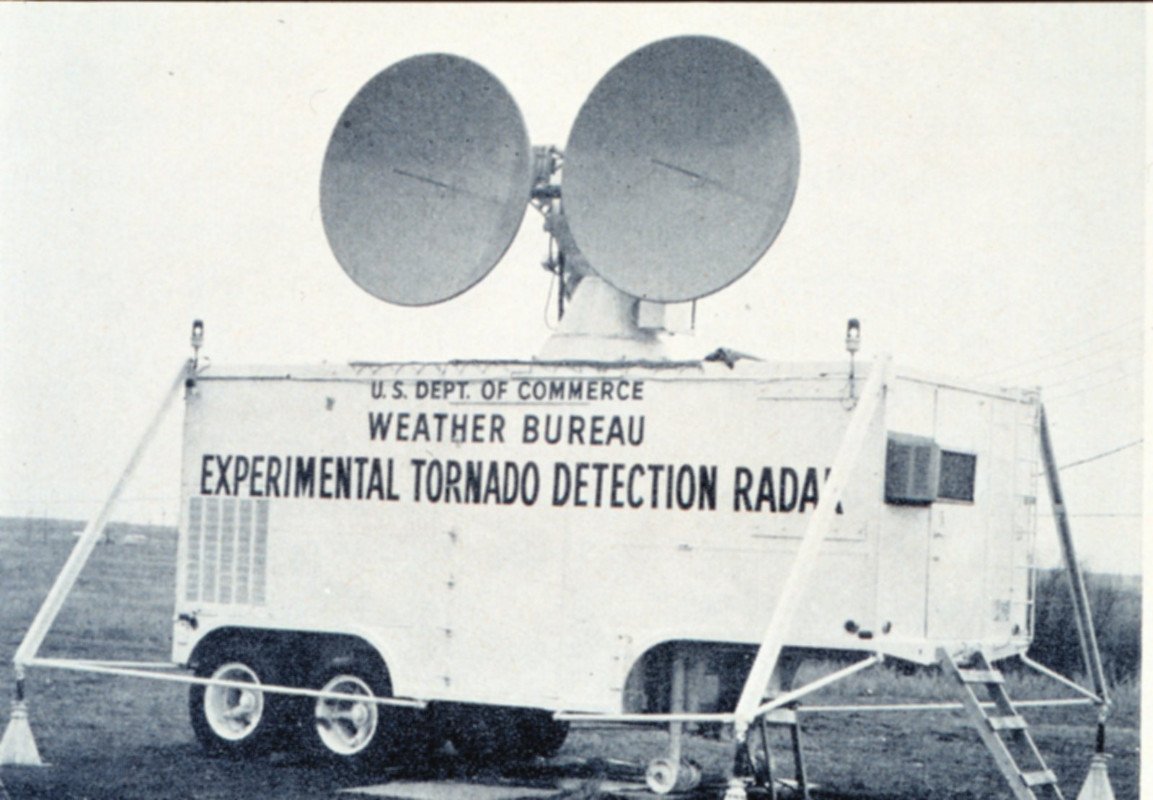

The Weather Bureau’s first experimental Doppler Radar unit. The Weather Bureau officially began as a part of the Department of Agriculture. In 1970, it was renamed the National Weather Service and moved to the newly created National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). (Photo credit: NOAA)

NOAA’s National Ocean Service, which houses its Coastal Zone Management (CZM) program, would see a 50 percent cut if the administration’s plan is implemented. Such a deep cut, said Brockbank, means losing protections for coastal restoration and habitat conservation, which could have a long-term impact on fisheries.

These proposed budget cuts and layoffs follow resignations or layoffs of 1,300 NOAA employees in March, hobbling the agency’s ability to carry out its mandate. Though hundreds of NOAA employees were subsequently reinstated, the attrition continues. The Northeast Fisheries Science Center, for example, reported in early May that it has lost more than one-quarter of its staff.

The President’s May 2 proposed “Skinny Budget” for fiscal year 2026 calls for the same $1.3 billion cut to NOAA, but provides scant details on specific programs to cut. “The details are so confused, but the underlying thread is that they’re slashing these scientific agencies that provide critical services to the American people, and they don’t care what the impact is,” Andrew Rosenberg, a former deputy director of NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service, told Civil Eats.

Budget negotiations are ongoing between Congress and the President, and however they resolve them, the administration’s April 17 executive order entitled “Restoring American Seafood Competitiveness” confirms its clear desire to upend the fishery management system that has not only kept American fisheries relatively healthy for decades, but has served as a model for fisheries management globally.

“The hard-won progress over the last 30 years to rebuild most of our fisheries—from in many cases severe depletion—could very quickly be reversed if we’re not going to enforce the rules or manage the fishery,” said Rosenberg.

When asked how NOAA will ensure the long-term sustainability of U.S. fisheries with a diminished staff, a spokesperson for the agency, James Miller, responded, “Per long-standing practice, we are not discussing internal personnel and management matters, nor do we do speculative interviews. NOAA remains dedicated to its mission, providing timely information, research, and resources that serve the American public and ensure our nation’s environmental and economic resilience.”

“The hard-won progress over the last 30 years to rebuild most of our fisheries—from in many cases severe depletion—could very quickly be reversed if we’re not going to enforce the rules or manage the fishery.”

Many in the industry were hoping for a more measured approach to reforming the lengthy process for setting fishing rules. “Everybody would agree, a lot of key reforms are needed within NOAA, but it’s a place to go with scalpel and intent,” said Ben Martens, executive director at Maine Coast Fisherman’s Association.

And while fishing groups generally support the president’s executive order, which seeks to increase domestic seafood production and “unburden our commercial fishermen from costly and inefficient regulation,” they say that any loosening of the rules must be done carefully to prevent a return to the Wild West days of overfishing.

“The devil is in the details, and that’s why it’s really important to have a funded and functioning NOAA and regional fishery management council system in place to implement the president’s vision,” said Eric Brazer, executive director of Gulf of America Reef Fish Shareholders’ Alliance, adding that fishermen must also be at the decision-making table.

The president’s budget proposals also call for eliminating NOAA’s Oceanic and Atmospheric Research (OAR) division, which collects vital, long-term temperature, carbon, and other data on our oceans and atmosphere, and abolishing all funding for climate-change-related data collection and research. Both of these functions are critical for understanding the health of the ecosystems that support U.S. fisheries.

Meanwhile, there’s greater need for research than ever, as warming ocean temperatures, driven by climate change, are shifting fish migration patterns and spawning behaviors. Warmer waters are also causing more violent and unpredictable weather that makes fishing riskier and damages critical coastal infrastructure such as wharves and piers.

Altogether, the staff firings, likely elimination of climate research, and NOAA’s compromised ability to forecast weather will fall especially hard on fishermen and coastal communities whose economies and cultural heritage are tied to healthy fisheries. Already, the impacts are beginning to play out.

Staff layoffs and retirements from NOAA’s fisheries division in March, plus a 60-day regulatory freeze, led to overfishing, slowed its ability to open fishing grounds this spring or keep them open, and sowed chaos.

Bluefin tuna was overfished by 125 percent in the mid-Atlantic region, because staff were unable to close the fishery in January when fishermen reached their catch limits.

For many fisheries to open for the season, NOAA’s NMFS must issue a rule with catch limits based on a “stock assessment,” an evaluation of the fishery’s health. A stock assessment can take one to three years to complete. NOAA fish biologists run surveys and models, collaborating closely with regional fishery management councils, state environmental agencies, other federal agencies, and sometimes international entities to conduct the assessments, a complex, data-driven system.

Sarah Schumann aboard Oceana. She and Dean Pesante fish out of Point Judith’s Port of Galilee in Rhode Island. (Photo credit: Dean Pesante)

John Hare, science and research director at NOAA’s Northeast Fisheries Science Center (NFSC), which covers North Carolina through Maine, acknowledged at an April regional council meeting that staff losses were impeding their ability to complete all 23 of its stock assessments scheduled for 2025. “It’s clear that we’re not going to be able to complete all of those,” he said, adding that his office intends to work with its partners “to come up with something that works for everybody.”

Indeed, New England’s lucrative scallop fishery—valued at $360 million in 2023—shut down midseason for a few weeks because NOAA wasn’t able to approve the rule proposed for 2025 on time. New England’s groundfish fishery (cod, haddock, and other species), valued at $42 million in 2023, was opened by an emergency action on May 1 while staff continued to finalize the rule.

On May 9, the NFSC and its partners announced that five fish stocks would not have full assessments this year as planned, and that it would pause research on two species, including winter flounder, which has been declining in New England partially due to warming waters.

“We’ve got fishing businesses that are relying on the passing of regulations, and if we don’t have the manpower to make those things happen, that can be really problematic,” said Martens.

Similarly in Alaska this spring, Linda Behnken, a fisherman and executive director of the Alaska Longline Fishermen’s Association, said “it was a huge scramble to get the fishery opened on time, with people not getting their permits until the day before, and the permits being issued wrong three times and having to be reissued.”

Senator Murkowski had to weigh in repeatedly with the secretaries of Commerce and State, according to Behnken, who added, “Things that used to just work are a mess.”

And in the Gulf region, Brazer said that his members are starting to see the impacts of a diminished NOAA. “Permit renewals are starting to take a lot longer,” Brazer said. “People aren’t there to pick up the phone when you call for support. We’ve seen our council meeting get rescheduled and shortened.”

The disappearance of seasoned scientists will likely affect the agency for years to come. Behnken worries what the loss of “really top people” from NOAA’s Alaska’s Fisheries Science Center means for the long-term health of Alaska fisheries, which produce most of the nation’s fish. Fewer staff to conduct stock assessments could erode NOAA’s ability to make sound management decisions around fish stocks.

“I’ve always believed that earning the title of commercial fishermen means more than just fishing. It also means standing up for the ecosystems that support our fisheries and the communities who depend on them.”

Robert Foy, Alaska Fisheries Science Center director, said at a regional fisheries meeting in April that while his staff were making “heroic efforts” to fill the gaps from lost staff and reprioritize work, “extreme changes and differences in the science that we are going to be able to provide” were looming.

Moreover, the center is operating under “a heck of a lot of uncertainty,” Foy said, as it tries to forecast its 2025 budget. The stock assessment and research projects currently planned may look very different when the group meets next in June.

Brazer, from the Gulf Coast fishery group, worries that the consequences of cutting or reducing surveys, dockside monitoring, and other data collection activities today won’t show up for years to come—and by then it may be too late to prevent a fishery from crashing.

Conversely, data gaps can also “lead to precautionary measures, which equals lower quotas,” said Steve Scheiblauer, a consultant to California’s Alliance of Communities for Sustainable Fisheries, a retired Harbor Master, and former member of the Pacific Fisheries Management Council. “That’s the chain reaction that folks are worried about,” he said.

Across the country, the worry is the same. “If there’s more uncertainty in the stock assessment process, regulators add a buffer,” agreed Thomas Frazer, professor and dean of the College of Marine Science at the University of South Florida and former chair of the Gulf Coast Fishery Management Council. “We don’t want to jeopardize the sustainability of the resource.”

Rosenberg, who helped rebuild New England’s scallop and groundfish fisheries in the 1990s, fears that the system may break down under such severe budget cuts. Rule setting will become slower and less comprehensive with fewer science staff, he said. A fishery may fail to open. Ultimately more fishermen may return to the old days of overfishing, especially if enforcement goes away.

“It’s not because [fishermen] are bad people,” he said. “They’re as profit motivated as anyone else. You could either fish hard or let somebody else fish hard. That’s why the rules are in place.”

Fishing is already one of the most dangerous professions. Fishermen are especially worried about cutbacks to NOAA’s National Weather Service, Martens said. “We rely on Weather for safety issues, and storms seem to be stronger,” he said, recalling the recent tragic loss at sea of a friend and board member of Maine Coast Fisherman’s Association.

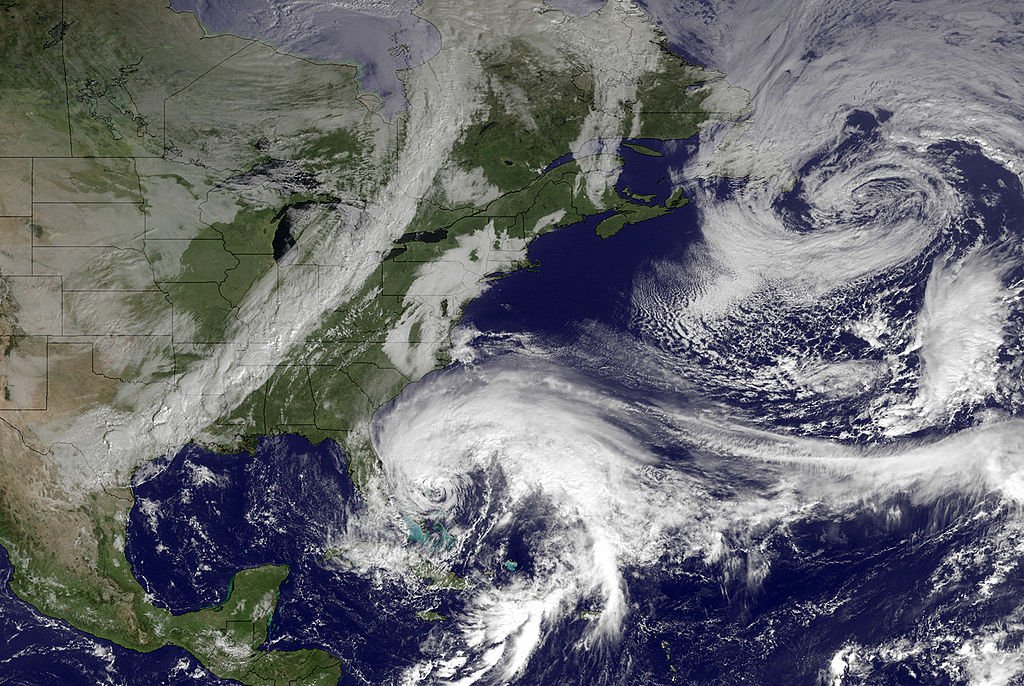

Hurricane Sandy’s huge cloud extent of up to 2,000 miles churns off the coast of Florida as a line of clouds associated with a powerful cold front approaches the U.S. east coast on October 26, 2012 in the Atlantic Ocean. (Photo courtesy of NOAA via Getty Images)

Since 2021, nine federal disasters from severe storms and flooding have been declared in Maine. Rainfall events in the northeast have also intensified by 60 percent over the last 60 years, bringing flash flooding to coastal communities.

Staff firings are already harming the National Weather Service’s ability to forecast. Thirty of its offices are now without a chief meteorologist, which has current and former agency meteorologists warning that life-saving advisories may not be issued in time for this hurricane season.

But the administration’s proposal would go even further: It would terminate NOAA’s role in producing weather forecasts for the public. Weather forecasting would be privatized, and fishers and the public would have to pay for a service that is now free. Worse, weather forecasting in areas not deemed profitable may cease to exist, Rosenberg said.

Weakening the National Weather Service also threatens coastal infrastructure, said Hugh Cowperwaithe, senior program director of fisheries and aquaculture at Maine’s Coastal Enterprise Inc. He cited massive, back-to-back storms that hammered dozens of Maine’s waterfronts coast a year and half ago and caused $90 million in damages.

“With people knowing it was coming, they were able to, somewhat, prepare,” he said. “But if these forecasters aren’t in place, and the predictions aren’t as good, I think we’re in for some real destruction.”

Similarly in Rhode Island, where Schumann and Pesante fish, Point Judith’s Port of Galilee is vulnerable to rising sea level and storm surges from ever stronger hurricanes.

“We’re a major port. We have shipping channels,” said Caitlin Chaffee, chief of Narragansett Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve, at the RI Department of Environmental Management. “That [weather] information all contributes to our port safety and helping those systems to run.”

Ocean temperature, salinity, carbon and ocean acidification data collected by NOAA’s Oceanic and Atmospheric Research (OAR) division feed into stock assessments to paint a holistic picture of the health of a fishery and its ecosystem.

NOAA’s OAR, however, is slated for elimination. Cooperative research institutions that help OAR collect climate and weather data, such as the Ocean Exploration Cooperative Institute in Narragansett, could also be shuttered. Removing climate data from stock assessments would hamstring scientists’ ability to understand and predict fish population dynamics as the ocean warms.

A fishing boat crashing through the ocean off the coast of South Carolina. (Photo credit: campbellphotostudio, Getty Images)

“Fish are highly responsive to thermal conditions. Everything that their physiology does is impacted by temperature and other environmental conditions,” said Halley Froehlich, associate professor of aquaculture and fishery sciences at the University of California at Santa Barbara. “If we don’t include those things, we’re not effectively managing [fishery] systems.”

Shutting down OAR’s collection of climate and weather data would make it harder to ascertain which factors most affect bluefish population dynamics in Rhode Island Sound, including warmer ocean temperatures, dredging to lay transmission cables for offshore wind turbines, water quality, and competition from other species.

It would also make it harder to model the dynamics of other species, such as lobster, fluke, summer flounder, and black sea bass, which are migrating north toward colder waters along the east coast, confounding fishery management decisions.

More broadly, OAR’s research is vital for understanding the many ways that climate change impacts both ocean and freshwater ecosystems. The division’s researchers, for instance, collect data that inform how warmer ocean temperatures and reduced snowmelt are shrinking the cold-water habitats that Pacific salmon need to thrive.

Their data sheds light on how warmer temperatures weaken the upwelling of nutrients deep in the ocean, reducing the abundance of the microscopic algae, or phytoplankton, that form the base of the marine food chain. And they trace how carbon dioxide, absorbed from the atmosphere, is acidifying the ocean, dissolving the shells of crabs and mollusks and decreasing the growth and overall health of juvenile salmon.

Schumann worries that NOAA may no longer be able to protect the ocean’s fisheries and the communities that rely on them. She has reason to worry. The president’s leaked April memo declares that the National Marine Fisheries Service, the division that issues fishermen their catch limits, should prioritize issuing permits to “unleash American energy,” such as oil and gas.

NOAA’s ship, the Thomas Jefferson, in New York Harbor. The ship is a hydrographic survey ship that maps the ocean to aid maritime commerce, improve coastal resilience, and understand the marine environment. (Photo credit: NOAA).

Also, Trump’s April 17 executive order calls for opening up the Pacific Islands Heritage Marine National Monument, the world’s largest ocean reserve and home to endangered sea turtles and whales, to commercial fishing. President George W. Bush established the monument, which lies 750 miles west of Hawaii, in 2009. President Barack Obama expanded it in 2014.

Without a strong NOAA, “you’re going to see a situation where the biggest money, the biggest power, talks,” said Brockbank of the Coastal States Organization. Similarly, for onshore development, with no funding or staff to support coastal zone management, “you’re going to allow for large industrial projects that have billion-dollar investments to be pushed through without local fishermen having an ability to influence that,” he said.

Moreover, he continued, “If you don’t have the funding to support . . . coastal zone management, you will lose some of the protections and some of the advances in restoration and habitat conservation, which could have longer-term impact on fisheries.” Coastal estuaries provide nurseries for fish and shellfish and habitat for other animals, while also filtering out water pollutants and buffering communities from storm surges and floods.

For coastal Rhode Island, the threat looms large. “It’s our tourism and recreation, our fisheries, our aquaculture. All these multi-million-dollar industries depend on a healthy estuary—and things that folks may not appreciate, like water-quality monitoring. [That data] helps us decide when it’s safe to eat shellfish,” said Chaffee, whose budget—for now—is 70 percent NOAA-funded.

While some may think that a weaker NOAA is better for fishermen, that’s not how Schumann sees it.

“I’ve always believed that earning the title of commercial fishermen means more than just fishing. It also means standing up for the ecosystems that support our fisheries and the communities who depend on them.”

July 30, 2025

From Oklahoma to D.C., a food activist works to ensure that communities can protect their food systems and their future.

Leave a Comment